Silent crime stories from the vaults

Over the course of the last twenty years or so, we Danes have increasingly come to consider the crime genre something of a Danish – or at least Nordic – specialty. Series such as 'The Killing' and 'Bron/Broen' ('The Bridge') and the Department Q films have enjoyed great success, and publishers have unleashed an endless barrage of crime fiction onto the Danish people.

Peter Schepelern, Associate Professor | 12 January 2021

However, back in the golden age of popular film – from the 1930s to the 1950s – the crime genre was something of an anomaly in Danish cinema. Admittedly, back in the 1940s one finds a small handful of ‘noir’ dramas – films like Afsporet (Derailed), Mordets Melodi (The Melody of Murder) and John and Irene. But these were exceptions: overall, brightly cheerful and convivial folk comedies were the order of the day. Still, one should not overlook the fact that early Danish film – silent movies – certainly had an eye for crime and punishment. That is the subject addressed here.

Back then (as now), crime was heavily reported in the daily press. And the reporters did not pull their punches. Journalism from the first decades of the twentieth century abounds with sensationalist accounts of horrific, bloody crimes. At the same time, the crime novel entered the realm of Danish literature when Palle Rosenkrantz, an author working with genre and pulp fiction, came up with the first Danish crime novels: Mordet i Vestermarie (Murder in Vestermarie, 1902) and Hvad Skovsøen gemte (The Secret of the Woodland Lake, 1903). Notably, the serious writers of the period were reluctant to portray crime. It is true that a murder is committed in Jakob Knudsen’s Den gamle Præst (The Old Rector, 1899) and in Sind (Mind, 1903). However, a figure such as Henrik Pontoppidan, whose extensive written oeuvre encompasses all of Danish society, only touches on the subject in quite a peripheral manner (his novella Thora van Deken involves a fraudulent will).1 And even though the young Johannes V. Jensen wrote crime stories of a kind before he got his breakthrough as a serious writer, he typically did so for pulp magazines under a pseudonym. The best of these stories, Milliontyvenes Høvding eller Den røde Tiger (The Chief of the Thieves of Millions or The Red Tiger, originally from 1897), was not published in book form until 1990, when it was released by the prestigious publisher Gyldendal.

It begins with crime

Crime belonged to the realm of low culture, making it an obvious choice of subject matter for film, the new low-culture popular medium. Tellingly, a 1908 article in the Danish daily Berlingske Tidende on the subject of ‘A Misused Invention’2 criticises the film medium for, among other things, presenting ‘horrifying murder mysteries’.

In fact, Danish film history begins with crime. In the first-ever Danish fiction film, Peter Elfelt’s The Execution (1903), a female child killer is taken to be executed. Allegedly, the story concerns a French case; in Denmark, the last execution took place in 1892. Sadly, only two minutes of the film survive. We do not see the crime, only the overture to the punishment. Even so, crime is firmly established as a theme in film here.

Crime and criminals were regarded as excellent subject matter, not least for silent films which, for obvious reasons, focused on the physical aspects of things. Established in 1906, Denmark’s new – and leading – film company, Ole Olsen's Nordisk Films Kompagni, was very much aware of the visual potential of the genre. The year 1907 saw the release of Viggo Larsen’s crime film Røverens Brud (The Robber’s Bride), in which the chief robber (played by Storm P., best known for his cartoons and humorous writings) is reported to the police by a gang member who has been rejected by the robber’s wife. She goes on to shoot the turncoat and break her husband out of jail, but the couple are eventually defeated. A western-style criminal romance, modelled on cinematic styles from abroad.

The same year also saw the launch of the now-lost Mordet på Fyn (Murder on Funen, director unknown), which was based on an entirely topical murder case that had received extensive media coverage: On 9 April 1907, an 18-year-old girl from Middelfart was found with her throat cut. On 12 April, the case was solved: the killer was a 16-year-old farmhand.3 The film premiered on 18 April! Fast work indeed, but then again the film was only seven or eight minutes long.

However, the film was regarded as offensive by the Danish Minister of Justice, P.A. Alberti, who went on to introduce censorship in the Copenhagen area in order to prevent the screening of films in which ‘the practice of crime is depicted’.4 Similarly, Alberti also sought to prevent the filming of Viggo Larsen’s infamous Lion Hunting (1907, premiered in Denmark 1908). The whole thing came across as the cultured bourgeoisie’s rejection of a new, sensationalist media. But suddenly the roles were reversed: shortly afterwards, it turned out that the minister was himself a criminal. He was convicted of the largest-ever fraud in Danish history – embezzlement and forgery to the value of DKK 15 million.

Criminals on film

In Danish silent films, the crimes perpetrated are – very aptly, given the backdrop of Alberti’s activities – usually about enrichment: thefts, robberies, frauds. But there are also stories of human trafficking, of kidnapping and abduction, of arson and smuggling, of espionage for foreign powers and of political persecution.5 Such stories can be served up in many ways: dramatic, melodramatic, comic, tragic. And the films were helmed by the very best directors of the era. It would seem that no-one looked down their noses at the genre: its practitioners included August Blom, Urban Gad, A.W. Sandberg, Holger-Madsen, Robert Dinesen, Benjamin Christensen, not to mention Carl Th. Dreyer. The latter’s debut, The President (1919), revolves around crime and punishment, and sixteen out of the twenty-films he authored prior to his own directorial debut also deal with crime in one form or another.6

Denmark has a tradition of calling such films ‘forbryderfilm’, literally ‘films about criminals’, because they are not crime films in the usual sense of following an investigation of a crime. These are not whodunnits which build up to the great reveal of the killer’s identity, as would later become a standard structure of the genre. Silent films initially showed the criminal in action right from the beginning, and the plot then typically centred on capturing him/her.7

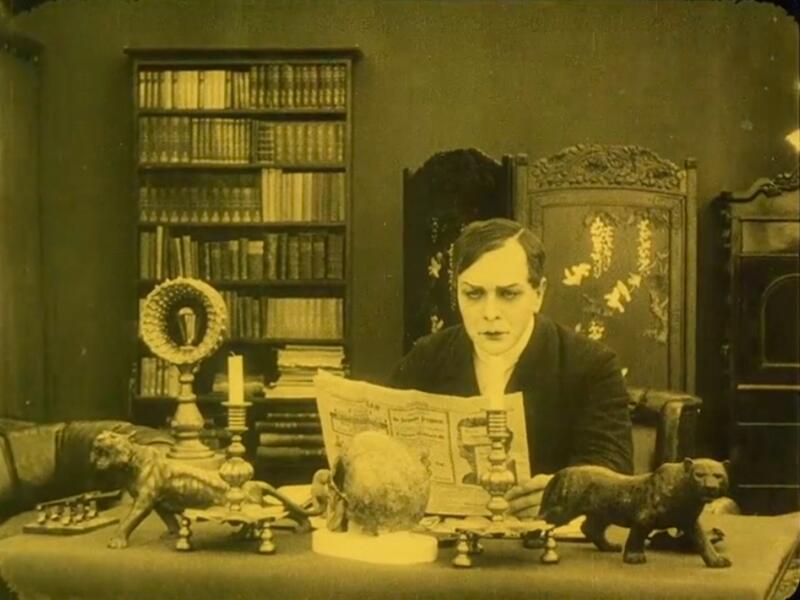

The stories are often set among well-dressed people in stately homes, amidst distinguished, dark living rooms crammed with fine furniture, large mirrors and paintings on the walls (the same painting can be spotted in The White Slave Trade, In the Hands of Impostors and Temptations of a Great City!). Of course, there were plenty of servants around to ensure that these polite and cultured people led comfortable lives. Then some outside threat would enter the picture: criminals intrude, sneak and swindle their way in, usually to partake of the wealth of the bourgeoisie. There is usually a safe or jewellery box ripe for plucking.

Mastermind

So who is the criminal? He or she may be a mysterious, demonic figure, a criminal mastermind who commits complex and cunning crimes with the aid of various henchmen and minions. A literary archetype known from figures such as the French Fantômas, the German Doctor Mabuse and more recently the James Bond villain Blofeld, all of them literary figures since adopted by the world of film.

Villains of this ilk appear in Danish silent films such as Dr Nicholson and the Blue Diamond (1913), about an eccentric criminal mastermind who, via a rather intricate intrigue involving a false marriage and an impoverished count, sets out to steal a precious diamond. In August Blom’s The Spider's Prey (1916, manuscript by Dreyer based on a novel by Sven Elvestad / Stein Riverton, a Norwegian pioneer of crime fiction), a charismatic, captivating woman controls the criminals. And in Karl Mantzius’s Pavillonens Hemmelighed (Secret of the Pavilion, 1916, manuscript by Dreyer), a sinister count plans to purloin the crown jewels. The type is especially prominently featured in the period’s three crime series: Gar el-Hama, The Man with the Missing Finger and The Daughter of Darkness, of which only the last part of The Daughter of Darkness is currently available.8

The ‘Oriental Poisoner’ Dr. Gar-el-Hama (Aage Hertel – back then no-one had any compunctions about letting a Dane play an Egyptian villain) appears in five films (1911–18). John Smith, known as The Man with the Missing Finger (also played by Aage Hertel!), similarly appears in five films (1915–17) while the adventuress known as the Daughter of Darkness (Emilie Sannom) stars in four films (1915–17). The structure is the same: with the help of minions and accomplices, the cunning criminal commits one crime after another, and even if he/she is caught, they escape time and time again. Typically, the first Gar-el-Hama film, Eduard Schnedler-Sørensen’s A Dead Man’s Child (1911), ends with the criminal being thrown from the roof of a speeding train, breaking his neck in the fall. But in the second film, Dr. Gar-El-Hama II (1912), he turns out not to have died after all ...

With this, one might say that Danish crime series was established, a format which was not taken up again until Leif Panduro’s TV series Ka’ De li’ østers (Do You Like Oysters, 1967, directed by Ebbe Langberg).

Detectives at work

The opponents fighting these villainous characters was typically a detective – the detective genre was hugely popular at the time. Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes was the main idol with his ingenious deductions and peculiar personality. Several early Danish films quite overtly named their detective protagonist Sherlock Holmes, even though they are unlikely to have cleared the appropriate rights: Sherlock Holmes i Livsfare (Sherlock Holmes in Mortal Danger, 1908), The Confidence Trick (1910), The Count’s Double (1910), The Black Hood (1911) , the fragment Hotel Thieves (1911) and The Stolen Legacy (1911). In other films, the detective’s appearance quite obviously references Holmes, and the character bears an English name: Pat Corner, Newton and Watson (!), Sylvester Jackson, Mac Irwing, Tom Barker.

We often appear to be transported to an English-speaking universe, even if the setting do not exactly bear this out. In The Secret of the Night Express (1917, unknown director) a text claims that the New York Express is passing by, but the station features a sign from De danske Statsbaner – Danish Rail. In August Blom’s The White Slave Trade (1910), the hero sets out for London to free his abducted girlfriend with the help of a local detective – and the imprisoned girl is shown to be held captive in a room with a window overlooking a rather naively painted backdrop depicting Big Ben. When the first rescue attempt fails, the criminals try to escape on a small boat, but are overpowered, and the boat docks in, of all places, the port of Elsinore. A rather idiotic approach, one might think, but surely no more idiotic than a modern film like The Danish Girl, which shows mountains in Southern Jutland and has Copenhagen’s Marble Church suddenly appear in Paris.

In Viggo Larsen’s Pat Corner (1909), the cunning criminal disguises himself as a blind old man with crutches. Going via a pub, he gains access to a barn where he casts off his crutches and opens a trapdoor in the floor. We then see – in an interesting cross-section of the location – how he has crawled through underground passages up to a thick wall leading to the basement vaults of a bank. He starts working on the wall, and the bank guard hears it: it’s quite funny to see a silent film use a sound element as a key element spurring on the plot! One might well think that the next move would be to call the police, but no: the guard reports the noise to the bank director, who in turn contacts detective Pat Corner. Together with his assistant, Corner quickly – but also extremely dramatically – solves the problem and arrests the villains. Along the way, views can amuse themselves by observing how the signage inside the pub is in English, while the streets outside carry advertisements for Danish beer types such as Stjerneøl and Carlsberg.

In The Count’s Double the thieves are cunning. They take clandestine photos of the titular gentleman, and based on this photograph one of the criminals disguises himself as the count. When the count leaves the house, the disguised thief turns up at the door. Incredibly, the servant accepts him as the master of the house (!), leaving him free to enter the drawing room and empty the safe. Fortunately, a cigarette left behind by the criminal gives Holmes all the clues required to find the culprit.

From naïve to knowledgeable

In these early, sometimes involuntarily comic dramas, often directed by Viggo Larsen, the narrative and technology both have a certain naivety that charms and amuses present-day viewers. Each scene is done as a single take, presenting a tableau-like full shot. The interiors are reminiscent of a traditional theatre stage with painted scenery, a stylistic contrast to the real-life locations of the exterior scenes. Sometimes, the fundamental rules of plotting and action seem to not be fully understood, such as when a train suddenly runs backwards in the film In the Hands of Impostors (1911). Gradually, however, the technical and narrative skill of Danish filmmakers grew in scope, leading to a marked increase in artistic quality.

For example, The Secret of the Night Express (1917) boasts a relatively complex narrative structure. It starts ‘in media res’: as a train comes whizzing through the dark, we see someone fighting in the open door of one of the cars and a figure falling from the train. The next morning, track workers find a dead man beside the tracks. The police are called, and Detective Tom Barker is put on the case. After a car chase, deputy director Braun is arrested and goes on to explain, in a long flashback, the events leading up to the present moment: his beloved Annie had been forced to marry the sinister director Wilson in order to save her father from ruin. It turns out that Wilton is a criminal scammer and brutal husband. In a sophisticated silhouette scene, Braun witnesses the state of the Wiltons’ marriage. And when he discovers that Wilton is on the same train as himself, he feels compelled to confront his enemy. We then return – by way of a framing device – to the introductory scene.

Somewhat later in the period we see the arrival of A.W. Sandberg’s virtuoso detective comedy The Hill Park Mystery (1923). Here, a young crime reporter, Brandt, feels a little overworked after having arrested a wanted criminal without the help of the police. Returning home, he fully intends to go on a much-needed vacation, but then – in a cut presaging the central scene of Antonioni’s Blowup (1966) – looks out from his window down at a nearby park only to become the horrified witness of a young woman knocking down a man. However, there is no body to be seen when he arrives at the spot. Later, having gone on holiday, he is introduced to the pretty daughter of a senior civil servant, only to realise with horror that she is the killer from the park. Of course, things are not as bad as they seem; this is a comedy, after all.

The enemy within

In most of the films, good people from polite society or decent common folk are beset by malevolent outside forces: demonic, criminal threats. However, sometimes the threat comes from nice people who turn out not to be so nice after all. As in Gorki (1912, director unknown) where a bank director’s own son turns out to lead a double life, partly as a clerk in his father’s bank, partly as the leader of a criminal gang.

Other stories are more psychologically interesting, focusing on a sympathetic character being dragged into trouble or even down into the abyss, often compelled by deep urges and desires. In Urban Gad’s famous The Abyss (1910), a genteel piano teacher (Asta Nielsen) is abducted by a juggler and follows him into the circus, where she turns out to have a surprising talent for erotic dance. However, upon being humiliated by her man she ends up stabbing her unfaithful and violent lover – partly in a state of passion and partly in self-defence. In August Blom’s Temptations of a Great City (1911), a young man from a wealthy family, living a life of idle comfort on his mother’s money, comes disturbingly close to becoming a criminal. At the very last minute he has second thoughts and reverts to being a devoted, well-behaved son again.

The train, the telephone and the trapdoor

It is quite striking to note how all these detective stories from the vaults of silent film use a number of frequently recurring elements and tropes. There is running and crawling and sneaking. There is flight and hot pursuit. The characters fall and swoon, are bound and gagged. They are locked inside chests, closets, basements and secret rooms offering few prospects of escape. They totter precariously on roof ridges, climb onto cornices and crawl on the outside of train carriages dashing ahead at full speed.

The preferred weapon is the pistol/revolver – even if it is mainly used to threaten and intimate. On the few occasions it is actually fired, the bullet rarely hits its mark even when the opponents are directly in front of each other. Bombs and so-called infernal devices are also used. And then there are all the significant small objects which are crucial to the action and trigger the rare close-ups: torn banknotes, an optical monitoring device, a drill in operation, a finger pressing an alarm button, a revolver pulled out of a coat pocket ...

Modernity is clearly in evidence, showcased by the rapid transport made possible by trains and by cars, preferably with new means of transport overtaking older ones. Motorcycles and speedboats also enter the fray.

Scenes are set in fashionable restaurants, at wild parties, but also in – the cinema, no less. There are ladies wearing very large hats (even indoors). And men with tall top hats and eyes rimmed with black makeup. There are disguises: villains and heroes both don various costumes, cunningly using false identities to gain access where they are not wanted. There is an abundance of letters and ‘tickets’ being exchanged, kept, saved, lost, stolen. It is as if the silent aspects prompts a penchant for communicating by written means. But modernity’s new, fast means of communication have a strong impact on the proceedings: almost all the films include telephones, using double exposures and split screens to convey phone conversations.

Then there are a slew of distinctive and unique methods, such as using a live snake to deliver a note to a prisoner via downpipes and gutters. And there is a wealth of secret passages through underground tunnels, hidden gates and trapdoors; you might even find a large trapdoor on the moors, leading down to a hidden underworld comprising several floors.

Worse than death

Films of this kind were launched as ‘thrillers’ or ‘sensational’ films; many of the era’s programmes use the term ‘sensationsfilm’. The commercial intentions were quite openly stated: this was about action and entertainment. Occasionally, one might also find aspects of a more idealistic – and social – nature, commitments which could, fortuitously enough, be combined with tantalising crime scenarios. Such traits are typical of the series of films focusing on defenceless young women being drugged, tied up and abducted, whisked off to a fate worse than death.

The trafficking theme was picked up at a very early stage with Viggo Larsen’s eight-minute Den hvide Slavinde (The White Slave, 1907) 9 and expanded upon to great success in subsequent popular sensational films, first in Alfred Cohen’s Den Hvide Slavehandel (1910), which no longer survives, but which Blom plagiarised to great effect that same year under the same title, The White Slave Trade, followed by Blom’s In the Hands of Impostors (1911) and The Spider's Prey (1916, with a manuscript by Dreyer) and Urban Gad’s The White Slave Trade III (1912). Here, nefarious men, aided by equally nefarious women, try to abduct young women and force them into prostitution abroad.

In The White Slave Trade III, the young variety show singer Ada approaches her theatre director to get her contract renewed. Sadly, the director behaves highly inappropriately (apparently this sort of thing happened in the 1910s, too), and she resigns. She responds to an advertisement announcing that a St. Petersburg variety show is looking for singers. But when she arrives there, it turns out that she has fallen into the clutches of brothel owners. Luckily, her lieutenant boyfriend also happens to arrive in town on a naval visit. Having vainly tried to enlist the aid of the Russian police (who, oddly enough, have a Danish map of Europe on the wall), he has to take the matter into his own hands.

People of all ranks could be affected by such heinous goings-on, as is evident from this programme text in which the film company offers comments redolent with social awareness:

In Series I of these pictures, we depicted how the ‘Trade’ behaved towards a young girl from the middle class. In the present series 2 we offer an account of how these scoundrels also let their grubby paws reach out for daughters of the so-called higher classes, young women who – when unfortunate circumstances leave them all alone in the world – are, generally speaking, less well equipped to fight against such dangers than the young middle-class woman, whose less restricted movements through life have unavoidably opened her eyes to many things that her supposedly better-situated sisters in higher strata of society do not face until disaster strikes (and then, often, it will be too late).10

However, the women are not only at risk of maltreatment at the hands of nasty pimps, but also from the distinguished gentlemen of the upper classes. In Dreyer’s The President (1919), it turns out that in his youth, the venerable, noble court president had made a woman of the common people pregnant and abandoned her – and the woman now sentenced to death for infanticide is his own daughter.

Literary deaths

The President was based on a novel by Austrian writer Karl Emil Franzos. Hardly anyone reads him today, but back then, reading Franzos sent a signal of cultural ambitions. This also applies to two other film adaptations, Robert Dinesen’s Hotel ‘Paradise’ (1917) and August Blom’s The Hand of Fate (1922, filmed in 1920), which are serious and gloomily melodramatic treatments of the crime/punishment theme.

Seemingly lost today, Hotel ‘Paradise’ was scripted by Dreyer based on a novel by the now-forgotten Einar Rousthøi. Writing about this book, the highly influential Danish critic Georg Brandes stated that it should ‘not be despised by the educated, even if it will be gobbled up eagerly by the uneducated’.11 It is about a German innkeeper couple who find themselves in dire financial straits, murder a rich guest and use the money to make a future for themselves, not least for their little girl, who – as one would expect from this sort of tale – grows up to fall in love with a young man who turns out to be the son of the slain.

The basis of Blom’s Hand of Fate, Steen Steensen Blicher’s short story Præsten i Vejlby: En Criminalhistorie (The Rector in Vejlby: A Crime Story, 1829), is a major work in Danish literature12 and may be the first crime history in world history, having been written long before pioneering figures such as Edgar Allan Poe, Charles Dickens and Arthur Conan Doyle entered the scene. As many will know, the story served as the basis of the first-ever Danish-language sound film (1931); it was later adapted for a TV production in 1960 and filmed again in 1972. However, back in 1920 Blom also adapted the story, which is based on a true crime story from the seventeenth century about a temperamental clergyman who believes himself guilty of having killed a farmhand and is executed even though it later transpires that he was the victim of a conspiracy.13

Georg Schnéevoigt’s sound film version, The Vicar of Vejlby, is a sombre case informed by a dutiful deference to a classic piece of literature. The silent version – now once again available, which is something of a sensation in itself – has a similar feel, but also uses some surprising approaches: as the crime is solved via testimonies from the murder victim, who had not been murdered at all, it is told via flashbacks; a method that has since become standard procedure when the detective finally explains what really happened, especially in TV detective stories.

The execution itself is presented in a remarkable sequence where the characters are seen in silhouette: first the soldiers with the convict on their way up the hill, then the beheading itself. In Morten Piil’s guide to Danish film, Gyldendals danske filmguide, Schnéevoigt’s version is praised for ‘a single inspired idea: the prelude to the beheading, where the spectators are seen as silhouettes against the morning sky on their way up the gallows hill. Suddenly you find yourself in a Bergman movie!’14 Indeed, these visuals point towards the famous final Dance of Death scene in Bergman’s The Seventh Seal (1957). But the truly interesting thing is that the scene in Schnéevoigt’s version was simply lifted from the 1922 version and inserted in the new version as brief glimpses – without crediting the original source. It was not Schnéevoigt who was inspired, it was Blom!

Hotel ‘Paradise’ and The Hand of Fate can both be seen as reflections on the problem of punishment more than on crime. In Hotel ‘Paradise’ the guilty escape their punishment, in The Hand of Fate an innocent man is executed.

Just and unjust punishment

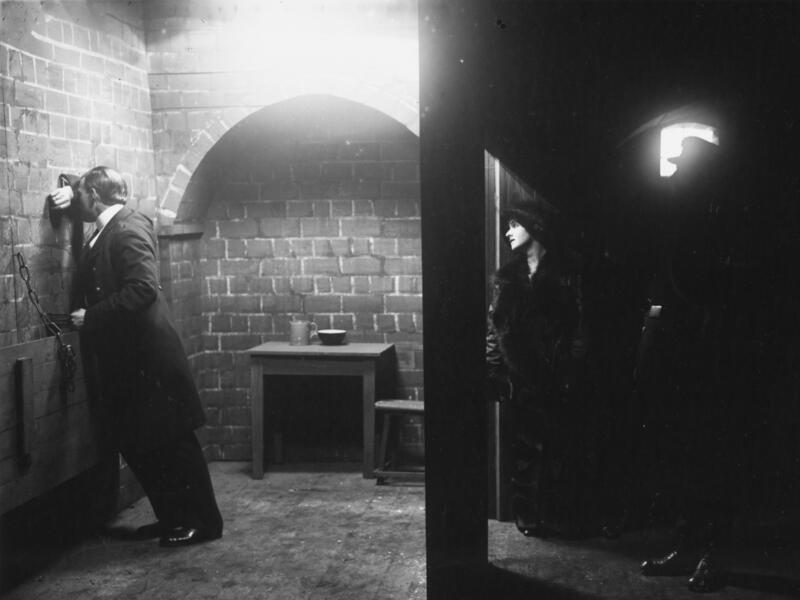

The films usually end with the arrest of the criminal. ‘The criminal is left in the hands of Justice’, as one programme said.15 The case is solved, the wicked are taken away, and the good have their lives restored to them. Sometimes, however, the stories turn their attention to the convicts and to prison life. In those cases, they typically focus on those who have been wrongfully convicted, an obvious basis for a touching melodrama.

One example is A.W. Sandberg’s The Power of Love (1919), in which a young woman turns in an aging gentleman who is on the run from the police. She does so to raise money for her sick mother’s treatment, but when the mother dies she puts the money in the church’s collection box instead. She also meets a young man who is the son of the fugitive. It turns out that the old man was innocent.

The theme is cultivated in two of the most popular and most admired films of the time. In Holger-Madsen’s morally edifying The Candle and the Moth (1915), a young man (Valdemar Psilander) is convicted of murdering ‘a lady of easy virtue’, as the programme puts it. He is innocent, but during his imprisonment – and inspired by the prison chaplain – he regrets his previously wild ways. After many years, his case is reassessed, and he is acquitted. The punishment was unfair, but still had a positive impact on him. He goes on to make a living as a lay preacher, telling his story to a young man who is on the path to wickedness. The young man’s unsuitable companions (which include Carl Schenstrøm before he became known as ‘Long’ of the comedy duo ‘Long and Short’) seek to pressure him into taking part in a burglary.

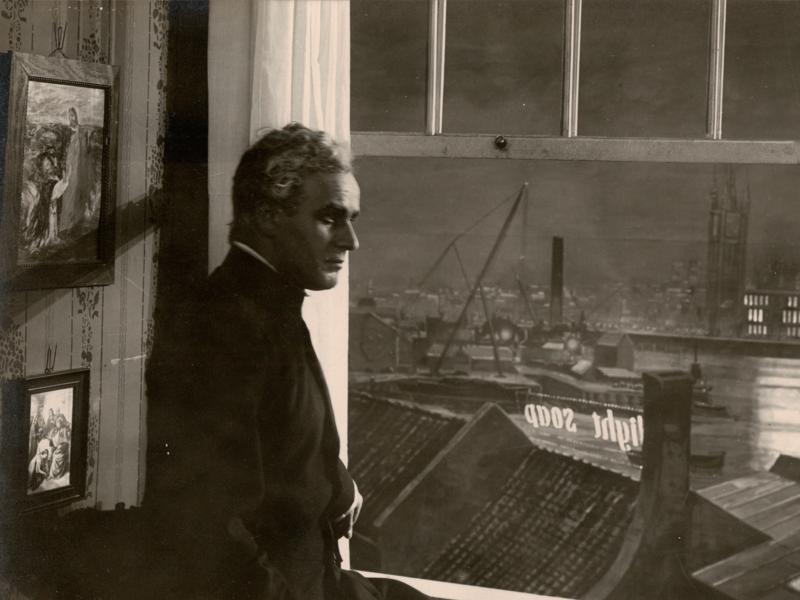

Another innocent convict character is that of Strong Henry in Benjamin Christensen’s Blind Justice (1916). Christensen himself plays the main role as a convict who escapes from custody and abducts his little boy from an orphanage. On New Year’s Eve, he seeks shelter at a manor house, where the young Ann believes his declarations of innocence and wants to help him. Unfortunately, he is discovered and arrested again – mistakenly believing that the young woman has betrayed him. Fifteen years later he is released in a somewhat demented state of mind. And now he wants revenge ...

The story is full of melodrama firing on all cylinders. The story is reminiscent of Dickens’s Great Expectations, which Sandberg filmed some years later (1922). Here, too, we find a dramatised and romanticised account involving an escaped convict and a little boy. Dickens certainly understood how to weave crime into melodramatic plots. This holds true of masterpieces such as Oliver Twist and Bleak House, but also Our Mutual Friend and Little Dorrit, which were filmed by Sandberg in 1921 and 1924.

Blind Justice is particularly noteworthy for its effective narrative style. There are traits of Griffithesque excitement in the last-minute rescue at the end, there are many changing locations, dramatic complexity, beautifully designed (English) intertitles with vignettes, superb lighting and scenography. The acting is melodramatic, yet infused with layers of significant psychological realism.

The telephone is a crucial plot mechanism. We see the telephone exchange operator in action on camera. The convict’s call lures a doctor away from his family – but the telephone also brings about the rescue. In the crucial scene where the father/doctor is tied up, his foster son, who has been locked inside a closet, succeeds in cutting a hole in the door with his pocket knife, freeing his father and enabling him to call for help over the phone. Christensen had already demonstrated his talent for such object-oriented, eminently cinematic scenes in Sealed Orders (1914), where the spy is caught under a trapdoor.

The end of an era

Crime movies come to a stop in Denmark in the early 1920s – and a rather sudden stop, too. Danish film was waning; the great years were over. The last two crime films, both by A.W. Sandberg, are On the Stroke of Midnight (1923), a ‘Crime Story in Five Acts’ in which a young man and a young woman each take the blame for the death of a villainous district attorney, and the comedy My Friend, the Detective (1924), in which ‘the bailiff’s daughter, the enchanting and dewy-eyed Miss Astrid, is an avid reader of detective novels’16 and tries her hand at being a private detective herself.

In 1931, sound film arrives in Denmark, first with remakes of The Hand of Fate and Hotel ‘Paradise’, both of which strike a dark tone. However, the darkness soon wears off as comedies and light entertainment take over. Some may think this rather a punishment in itself. In any case, the time of crime had passed for the time being.

Notes

1. Swedish film adaptation, 1920, cf. Casper Tybjerg: ‘The Woman’s Point of View: ”Thora van Deken” (1920)’, https://www.kosmorama.org/en/kosmorama/artikler/womans-point-view-thora-van-deken-1920

2. 21.11.1908, quoted after Palle Schantz Lauridsen: Sherlock Holmes i Danmark (2014), p. 144.

3 See Politiken 9–13 April and 17–18 April 1907.

4 Quoted after Casper Tybjerg in Schepelern (ed.): 100 års dansk film (2001), p. 21.

5 Abduction: Ildfluen, Den sorte Kansler; arson: Herregaards-Mysteriet; smuggling: Madsalune; espionage: Det hemmelighedsfulde X; political persecution: Den sorte Kansler.

6 Dødsridtet, Bryggerens Datter, Juvelerernes Skræk, Den hvide Djævel, Den skønne Evelyn, Rovedderkoppen, En Forbryders Liv og Levned, Guldets Gift, Pavillonens Hemmelighed, Den mystiske Selskabsdame, Hans rigtige Kone, Fange Nr. 113, Herregaards-Mysteriet, Hotel Paradis, Lydia, Grevindens Ære.

7 Exceptions include Morænen and Paa Slaget 12, which build up to the reveal of the killer’s identity.

8 The following titles will be made available at stumfilm.dk: Dr Gar el Hama (1911), Dr. Gar El Hamas Flugt (1912), Gar el Hama III (1914), Gar el Hama V (1918), Manden med de ni Fingre I (1915) og Manden med de ni Fingre IV (1916).

9 Cf. Marguerite Engberg: Dansk stumfilm (1977), p. 120ff.

10 Den hvide Slavehandels sidste Offer, programme.

11 Politiken, 24 December 1914.

12 Cf. The Danish Ministry of Culture’s Cultural Canon 2006.

13 However, subsequent research indicates that in all likelihood the priest was indeed guilty of the crime, cf. Mogens Møller: Præsten i Vejlby og hans søn – ofre eller mordere? (2017).

14 Morten Piil: Gyldendals danske filmguide (2008), p. 447.

15 Gar el Hama V, programme.

16 Min Ven, Privatdetektiven, programme.

Peter Schepelern, Associate Professor | 12 January 2021