It all begins with a movie theatre

Lisbeth Richter Larsen, Editor | 21 March 2022

Copenhagen city centre, 1905. He was on his way to the States, actually – that was his dream. However, on the first stop of the journey, whilst visiting his sister in Copenhagen, he spotted a newspaper ad in which they were looking for someone to work at the Biograf-Theatret cinema in Vimmelskaftet. Young Axel Sørensen, who’d just turned 20, shows up in his brother’s presentable trousers and gets the job. Now he’s holding the crank handle lightly and running the film through the projector. The pace and rhythm are of vital importance. His back is dripping with sweat, but he’s good at his job. The audience in the theatre is guffawing at the French farce flashing across the screen.

His colleague Viggo Larsen is in the foyer, selling tickets for the next screening. He’s 25 and has the rank of a sergeant, but he was a bit too “Bohemian” for the military. He likes to make things happen, and he loves to perform. The blood of an adventurer runs through his veins; he wants to go to the Congo and quit his military career at the Frederiksborg Castle School for non-commissioned officers. For reasons unknown, he starts working at Ole Olsen’s brand new cinema at Vimmelskaftet 47, and the Congo adventure is abandoned for an adventure of a different kind – film.

Inside his modest office, cinema owner Ole Olsen is racking his brain. Although running a permanent cinema is a novelty to him, the experience from his previous job as director of Malmö Tivoli, where he was also showing moving pictures, serves him well. The challenge is to procure enough films because the repertoire changes every week, and a cinema screening, which typically lasts 30 to 45 minutes, usually consists of four elements: “pictures of nature”, a drama film, a report – most often on current affairs such as royal visits, funerals, Child Welfare Day and sporting events – and finally a comedy. All cinema owners face the same problem. The films have to be bought abroad, mainly in the UK and France, but soon they’re also being imported from the USA and Germany. The cigar is shifting back and forth between his tight lips. An idea is forming in his head – we can make the films ourselves, how hard can it be?

A community garden in Valby

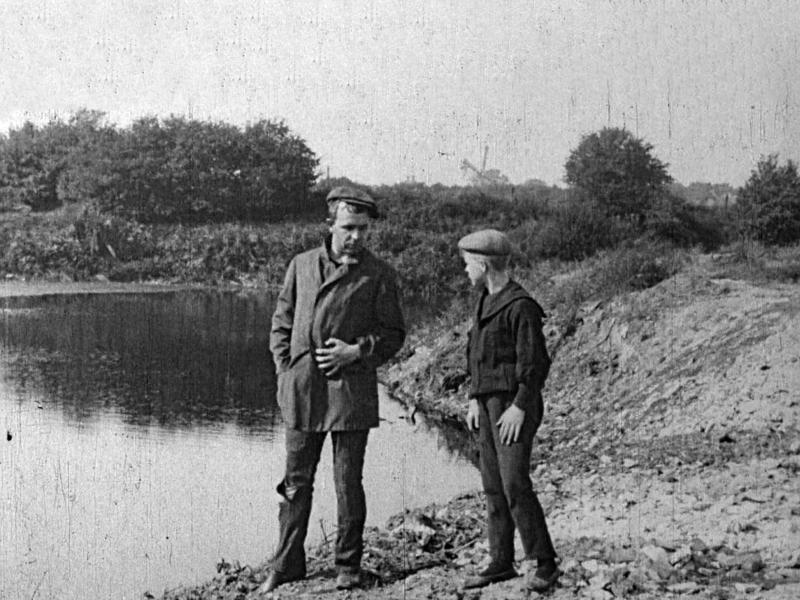

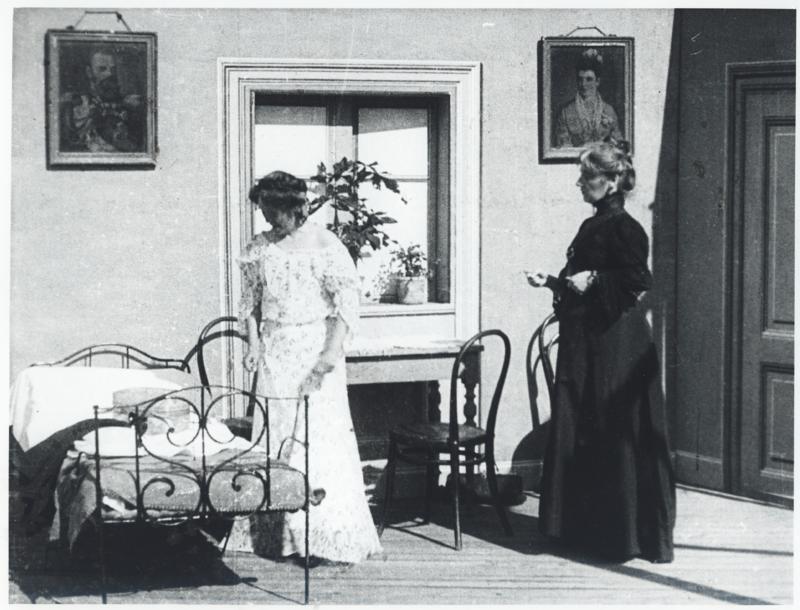

Valby, the spring of 1906. Ole Olsen has bought two film cameras from Pathé in Paris and a community garden on Mosedalvej in Valby. Axel Sørensen and Viggo Larsen relocate – now they’re working out in the open. Yes, they’re novices in film production, but they have important prerequisites that shouldn’t be underestimated: they’ve seen many films flash across the screen in Biograf-Theatret. It was the French and British films in particular that have provided inspiration for camera angles, editing, formats, acting, and the like. Axel Sørensen becomes “chief cinematographer” with a good eye for the subject and, most importantly, a steady rhythm on the crank handle. Viggo Larsen can organise the “troops” both in front and behind the camera, and is also a talented performer in his own right, so he quickly jumps into the main roles himself, handsome as he is. Two birds with one stone – Ole Olsen likes that. The “stage” is a wooden floor with a simple railing around it, where primitive painted backdrops are hung. The first real film studio with a glass ceiling won’t be ready until the spring of 1908, so they’re left to the mercy of the wind and weather until then. The recording season lasts roughly from early April to mid-October, and sunlight is the only source of the film reel’s sensitivity to light. These are difficult conditions because the sunlight also causes undesirable shadows in the scenery, which can be seen in, for example, The White Slave Girl:

Playground and exploratorium

How did it start out? An idea, hastily scrawled on a piece of paper, a camera at the ready on a tripod, and a bunch of enthusiasts who rolled up their sleeves to offer what they could? The short answer is: Well, they simply did it.

As early as 15 September 1906, Ole Olsen was able to present his own first purely Danish cinema repertoire. At that time, they’d already made about 30 short action films or “arranged films”, as they were called:

- Between Monkeys and Bears (footage from the Zoo)

- The Life of Fishers in Scandinavia (a drama in which a young fisherman, Viggo Larsen, loses his life at sea and is followed to the grave by his family in the small fishing village)

- The Bastion War (footage of the military drills at Copenhagen’s fortifications)

- A Gift to my Wife (a drunk man comes home to his wife and gets beaten).

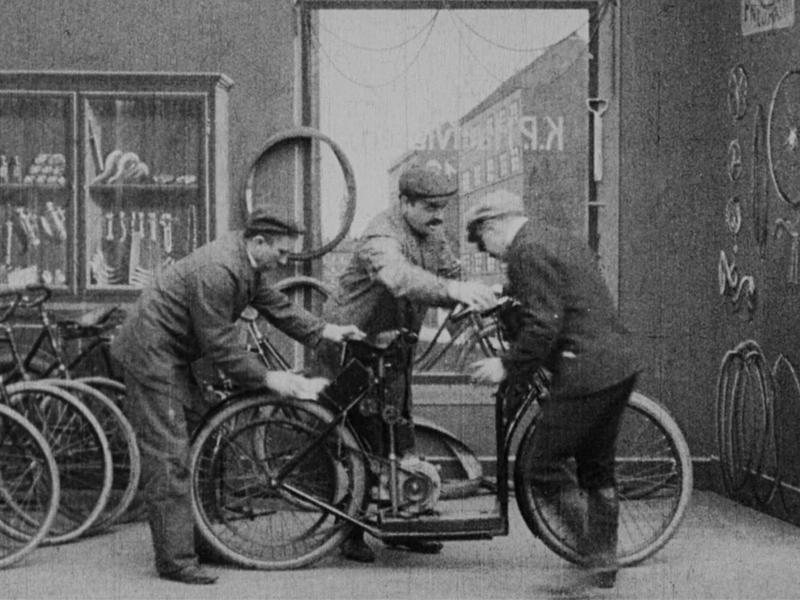

The first films were mostly shot “on location”. They frequently used the immediate surroundings: Søndermarken Park and residential streets in Valby and the slightly wider old road to Køge (Gl. Køge Landevej) for “transport images” and car chases. One of the earliest films from 1906, The Other Woman, a violent drama about jealousy, “cuts” deftly between the married couple’s and the other woman’s villa (the camera was placed on the pavement just outside the garden gates) and two places in Søndermarken. The idea, i.e. setting of the narrative, and the dramatic ending – a shooting duel with the inevitable slow-reacting victim, followed by a shooting and then suicide – unfolds in just five minutes. It’s simple and amazingly efficient. So wonderfully innocent, so delightfully baroque.

They also picked locations that matched the story more accurately. In the 18th century comedy From the Rococo-Times, made the following year, a large team of actors travelled to Hillerød to film in Frederiksborg Castle Gardens. It must have been both time-consuming and costly for the entire crew to take the train. In addition to this, “historical films” required the renting of costumes – in this case wigs as well – so From the Rococo-Times was a bit of an investment. The actors were usually expected to bring along costumes. There’s a single indoor scene, which is used twice in the film. It is set on the suspended wooden floor in Valby, and the wind was obviously whistling around the stage that day because the set pieces flutter merrily in the background:

The fourth musketeer – Storm P.

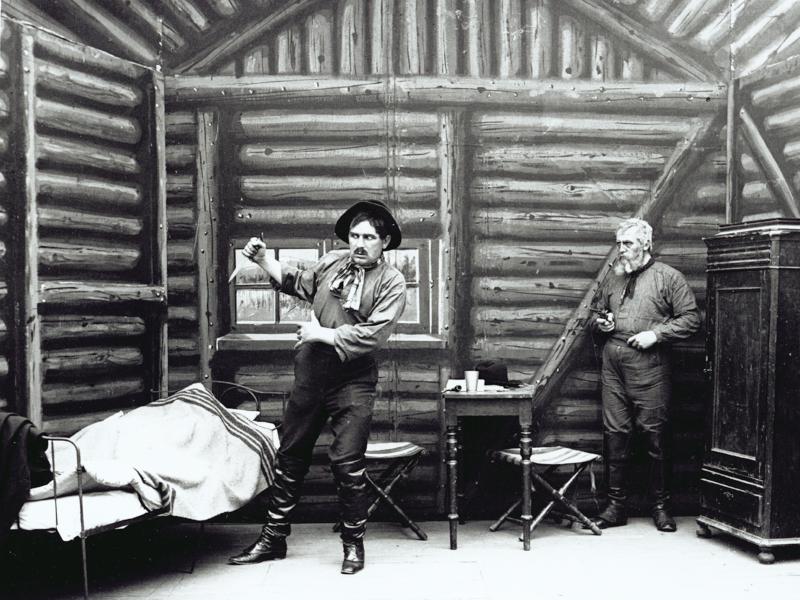

A Jack of all trades, artist Robert Storm Petersen had been there from the outset. As illustrator, painter, actor and writer, he found film an obvious playground for his many talents. A man named Robert Krause painted the backdrops, which were nailed directly to the railing that enclosed the suspended stage floor. That’s where Storm P. lent a helping hand, as did the others who were present. They used wallpaper and painted everything directly on it – windows, shelves, and rows of hooks. The result was quite characteristic flat backdrops that we notice in the early years of film. In The Robber’s Sweetheart, everything is painted, except for the door that can be opened, and the table and chair. The woman is even looking out out of the painted window:

Storm P. also appears as an actor in many of the films. He stands out from the others in that he actually looks like he’s having fun and in his element at the same time. A small and nimble body and wonderful details, such as in Once Upon a Time, where he, wearing a pair of oversized shoes, tumbles down the stairs from the throne twice.

It’s got nothing to do with the action, but he’s having his own little party. It is a shame that Jeppe of the Hill hasn’t been preserved – in it he plays the bailiff’s wife! Storm P. was paid DKK 5 a day, just like many other actors. He retired from filming before the 1907 season ended. “I just think it’s all become too businesslike with inspectors and real actors and directors and all that was […] improvised disappeared” (Berlingske Tidende 8 April 1923). Business and efficient production flows weren’t the creative anarchist’s cup of tea.

The actors and their acting

It’s difficult to determine exactly how many films Viggo Larsen made for Nordisk Film, but it’s safe to say that it was at least 200. On top of that, he appeared in front of the camera in about 70 dramas and comedies. Although there was a fairly steady team of “actors” from the start, they were by no means recruited from the city’s theatre scene because film acting was considered a contemptible occupation. Apart from Sergeant Larsen and the slightly more experienced Storm P., who was employed at the Casino and Dagmar theatres whilst he was filming, ventriloquist Gustav Lund appeared in more than 50 films. Clara Nebelong was a trained organist, but she entered the world of theatre because she was married to Axel Boesen, who also worked as an extra and took on minor roles at Nordisk at an early stage. Agnes Nørlund was a ballet dancer. And then there were all those who leaned over the fence in Valby and were occasionally asked to step in.

The overall impression of the acting in the early years is that of a pantomime and an over-the-top acting style. Wild gesticulations, dramatic make-up and clumsy scenes. Extras and others often look directly into the camera, whilst overweight men hiding behind overly narrow trees without being detected just seems silly. However, the actors had to find a new silent form of expression, and strike the right balance for how it would work on the screen. Those experiences imply an occasional mishap behind the scenes. References to and reviews of Danish films abroad, however, were a sign that things were about to get better. For example, The Stepmother is mentioned in an American market journal in the following terms: “The story is clearly told and the action, as in all the late productions of this company, is not overdrawn, but natural and easy”. The film is also praised for its “excellence of the photography” and the details of the produced scenes (Moving Picture World, 9/1/1909).

So, 1909 was the year of overcoming the inevitable teething troubles. Better-educated people would soon be joining, among others, a very young Elith Pio, who later had a long and varied acting career, and Petrine Sonne, who played the role of the incredibly ignorant nanny in the silly slapstick farce The Short-Sighted Governess. A curious detail is that the film ends with a close-up – completely out of the overall context. Is this the first close-up in Danish cinematography? Has Axel Sørensen stepped into the experimental corner here?

The man with the crank handle

Axel Sørensen is a completely indispensable talent in the early years. He has a flair for working with the camera and is constantly developing his craft. He is looking at what the foreign cinematographers are doing, mimicked them, and tries to do it better. For example, he solves the tricky shots, which can be seen in movies such as The Tinderbox and The Witch and the Cyclist, by stopping the crank handle just where he is supposed to in order to avoid both a clumsy “jump” in the film or a black screen. In The Child as Benefactor, the camera is moved closer to the actors, he tries to pan it, and the cutting rhythm is sped up a notch.

However, the primitive backdrops, clumsy acting and slowly unfolding narratives are still present in 1909.

The onward journey of the three-leaf clover

The year 1910 would mark a transition. A longer format of 20 to 40 minutes is introduced, so the stories have time to unfold. Two crucial talents enter the film scene in 1910: Asta Nielsen and Valdemar Psilander in The Abyss and The Portrait of Dorian Gray, respectively. Within a year, they’d both become renowned film stars worldwide. Nordisk Film hires new directors and cinematographers who make a serious contribution to its artistic development. Although Ole Olsen fails to get hold of Asta Nielsen, Psilander would become his golden goose for the next seven or eight years. The company expands with branches and sales agents across the globe, the polar bear logo is found on screens from Moscow to Rio, and production takes off from then on – and the rest is history, as they say. Even today, Nordisk Film is located in Valby and continues to produce mainstream films for the whole world.

Axel Sørensen, who in 1910 changes his name to Graatkjær, continues to work at Nordisk Film until 1913, when he accepts an invitation from Asta Nielsen and her husband Urban Gad, who have become important names in German cinematics and want the best cinematographer for their production. His weekly salary of DKK 35 at Ole Olsen jumps to DM 3,000 per month at PAGU. He makes a plethora of films there and becomes a highly regarded cinematographer for the greatest German directors, including Ernst Lubitsch and F.W. Murnau.

Viggo Larsen, who left Nordisk in the autumn of 1909 after some disagreements with Ole Olsen, also moves to Berlin, where he enjoys a great career in German film. He works as both actor and director for several companies before starting his own. In the German film database he is credited as actor, director or producer of almost 170 films between 1910 and 1942. So, his film training at Nordisk Film from 1906 to 1909 has to that extent paid off if you squint at his impressive efforts in German cinematography.

Surprisingly little has been written about Viggo Larsen, and newspaper coverage has been scattered sporadically over the decades, mainly around anniversaries under headlines such as: “The sergeant who became a star”, “Forgotten world name” and “The soldier who became a star”. His essentially inferior film in 1907, Lion Hunting, most often features as Viggo Larsen’s work at Nordisk, and no one has properly researched his German career. The grande dame of Danish silent film research, Marguerite Engberg, was quite harsh in her assessment of Viggo Larsen’s efforts: he never fully developed artistically, he didn’t learn from his experiences, he didn’t feel the urge to play, which is a prerequisite for development, and he never succeeded in this and that. The verdict read: “He did equally well or, if you will, equally poorly in all genres.” Don’t we owe it to Viggo Larsen, who must be the Dane with the most films in his professional biography to date, to look again? As the Danish Film Institute digitises the silent film heritage and more of his films become available, and as the Germans have embarked on their own major digitisation effort that we can only hope will make some of his and many other Danes’ films available, we have one request: Watch his works, and judge his efforts with your own eyes!

Sources

Marguerite Engberg: Dansk Stumfilm I (which translates as Danish silent film, Rhodos, 1977).

The films available on stumfilm.dk.

Newspaper clippings from the Danish Film Institute’s collections and Mediestream.

The tape interview with Axel Graatkjær (Det Danske Filmmuseum, 28/12/1956).

Claus Ib Olsen and Philip Lauritzen: Cand.film in Kosmorama #94, December 1969.

Stephan Schröder: Kunst, skæg og ballade – Storm P. i den tidlige stumfilm (Kosmorama #281, februar 2022).

Lisbeth Richter Larsen, Editor | 21 March 2022

FIRST-HAND STORIES

On the occasion of Nordisk Film’s 50 year anniversary in 1956, DR (Danish Broadcasting Corporation) published a radio documentary with the title ’Bamse bliver 50 i år’, which translates into ‘The teddy bear turns 50 this year’. Hear Axel Graatkjær and Viggo Larsen tell their stories about how they became film pioneers.

Axel Graatkjær

Viggo Larsen

The four pioneers

Peter Elfelt films