Betty Nansen – a self-made woman

The great diva of Danish theatre, Betty Nansen, was the first Danish actress to be headhunted by the American film industry. And before that, Nordisk Film had given her a lucrative contract in the hope that the queen of theatre could become the new big film star. But was Betty Nansen ever successful on the silver screen?

Lars-Martin Sørensen, Head of Research Unit | 8 March 2023

Betty Nansen’s film adventure starts in 1911, when Nordisk Film’s director general Ole Olsen announces with great fanfare that he has signed a contract with her. At this time the star system first breaks through into Danish film – and, at roughly the same time, internationally. In the past, films had been sold based on their length and sensational content. Now the stars sell the films, and their names, not the names of the companies, appear at the top of the posters.

Nordisk Films Kompagni is in need of a female counterpart to the newly minted star Valdemar Psilander – a diva of the same calibre as Asta Nielsen. The company is mildly annoyed by her and Urban Gad’s success in Germany in the wake of their megahit with ‘Afgrunden’ (The Abyss) the year before. However, matching the offers that the couple gets in Germany is out of the question. Neither director general Ole Olsen, nor the other managers at Valby are especially fond of Asta Nielsen, her talent, or her appearance for that matter. But why not hire a truly famous and pretty face who is already enjoying great renown instead?

The new Sarah Bernhardt?

In 1913, theatre critic Axel Garde writes about Betty Nansen:

“You could make a cross-section through her roles, and in all of them you would find a moment when, with no gesture and no words, only through the life on her face, her smile, the look in her eyes, she gave the explanation, which said everything about the figure she wanted to bring to life.” 1

Garde clearly has no doubt: in Betty Nansen, Danish theatre had an actress of the same grandeur as Italy’s Eleonora Duse and France’s Sarah Bernhardt.

Already ten years earlier, American magazines had begun to write about the theatre diva Nansen as the great interpreter of the world-famous Henrik Ibsen’s female characters. And by mentioning ‘Ibsen’, one is also mentioning ‘The Modern Breakthrough’, i.e. talking about an artist who followed the late 19th century’s leading cultural figure and literary critic Georg Brandes’ dictum that the central task of art was to put current problems up for debate.

Ibsen’s female characters, from whom Nansen’s fame arose to a certain extent, were strong, independent but often also tragic characters. Just like the female protagonist, Nora, in Ibsen’s international breakthrough drama ‘Et Dukkehjem’ (A Doll’s House (1879)). Nora leaves her home, husband and children because she insists on being a human being in her own right – not just a doll in her (banker) husband’s posh home. With her – and with Betty Nansen – an icon of the women’s liberation struggle, which gained momentum in the late 1800s, was born.

The theatre diva as the queen of film

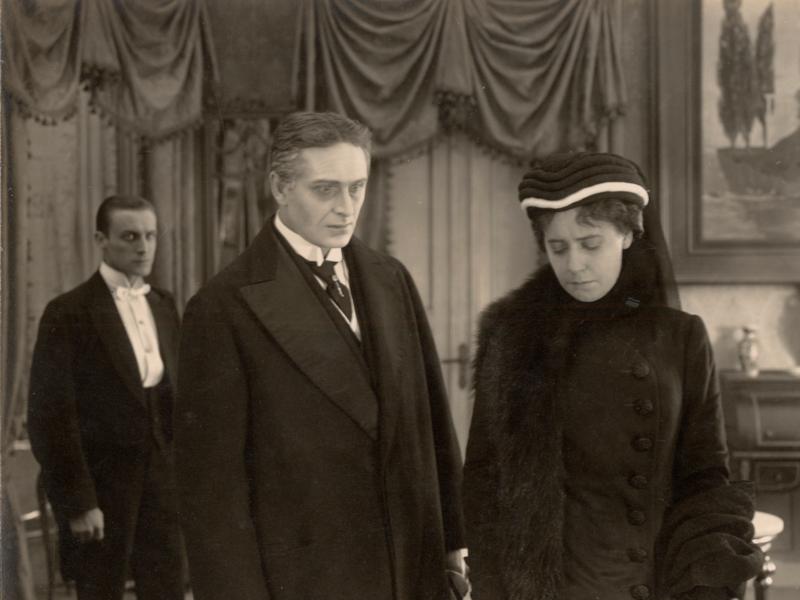

Betty Nansen makes her debut as a film actress with the tragic melodrama Bristet Lykke (A Paradise Lost) in October 1913. Nansen’s sudden leap from stage to film causes a certain polemic in both film and theatre circles. At this time, popular film has a somewhat tarnished reputation in so-called fine culture circles, but Betty Nansen sees the potential in reaching a mass audience and defends the new art form.

Already two years before her first film premieres, Nordisk’s American branch The Great Northern, begins to advertise the series of films that Nansen – the queen of Danish theatre – will star in. They give themselves plenty of time to build up expectations for Betty Nansen’s film debut, and Betty Nansen herself does the same by purposefully creating the exposure in newspapers and magazines that world fame requires. She likes to carry herself in a style worthy of a queen. For example, film historian Gunnar Sandfeld explains how Betty Nansen arrived for a shoot at Amager “in an elegant coach with two red coachmen and surrounded by handsome riding hussars, [and] had been greeted reverently by all the people, who thought she was the queen, the real queen.”2

Mrs Nansen also gets royal treatment in the programme for her first film ‘Bristet Lykke’ (A Paradise Lost (1913)). The front page of the pamphlet bears the heading “Betty Nansen in Film”, and if you leaf through it, you’ll see two pages about Betty Nansen’s excellence as an actress. Only then follows the usual introduction of the film itself, which is the content that such programmes usually present. So, it’s a very special Nansen edition of a film programme that accompanies the first of the six films by which, according to her contract with Ole Olsen, she could command the princely salary of DKK 42,000 to shoot through 1913 and 1914.

Betty Nansen is marketed as someone very special and also directly promoted by the company’s director general Ole Olsen himself. He gives an interview in August 1913, having just returned from Berlin, where he has spent time “down there to show the first Betty Nansen films. The Germans were speechless with excitement, but Mrs Nansen is also the greatest film actress in the world,” Olsen says. To this, a curious journalist asks if it isn’t Asta Nielsen who is the greatest? Olsen dodges the question by answering that the two are as different as night and day, but that next year Nansen will “be the artist the whole world is talking about.”3

Filmed theatre

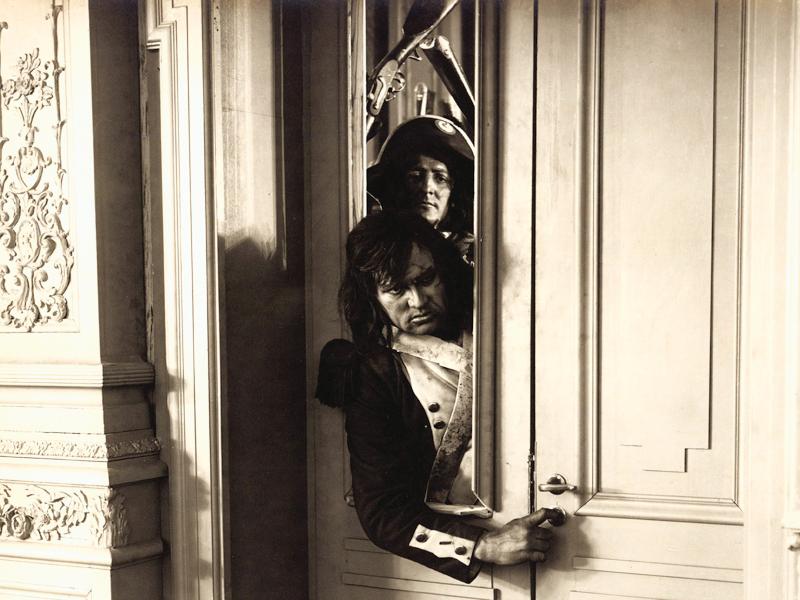

The agreement with Nordisk Film means that Nansen has some control over which roles she will play and who will deliver the scripts. A common feature of Nansen’s Danish films is that she plays a strong, but often suffering and self-sacrificing heroine – maintaining her image as an interpreter of Ibsen’s female roles in the theatre, among other things. In relation to that, another great figure of the modern breakthrough, the daughter of feminist author pioneer Amalie Skram, Johanne Skram-Knudsen, is hired to write the script for Princess Elena (The Princess’ Dilemma (1913)). In this highly dramatic film tragedy, Nansen plays the princess who falls in love with a captured officer from an enemy army and dies for him.

A taste of Nansen’s acting skills and the way she was staged can be seen in the final scene , when she commits suicide in her prison cell. The suicide is beautifully filmed with slanted daylight, which falls through a high-placed cell window that Nansen turns towards so that her face is alternately illuminated and lies in semi-shadow, while she bares her wrist and finds the knife that will open the artery. The life slowly drains out of her as she stands, leaning against the cell wall, photographed so that you see her from slightly above the knees.

Betty Nansen in the final scene in 'Prinsesse Elena' (The Princess’ Dilemma. Holger-Madsen, Nordisk Films Kompagni, 1913).

The confidence in Nansen’s skills as a theatre actress shines through here, though it would be warranted to have a close-up of the dying princess, perhaps right into her face, to maximise the effect of her suffering. But the camera remains at a respectful distance while Nansen slowly slides down to the floor and exhales – still in full view which shows her body in full length, as on a theatre stage, where you can’t simply cut to the actors to communicate feelings with facial expressions. The scene appears as filmed theatre, which was certainly not what gave Asta Nielsen her great success in Urban Gad’s direction of Afgrunden (The Abyss).

Headhunted

Nordisk’s campaign for Nansen’s film via the company’s American New York branch, The Great Northern, bears fruit in a perhaps somewhat unexpected way: Betty Nansen is headhunted. In 1914, William Fox, the owner of the Fox Film Corporation, proclaims that “for the first time ever, a great European star was imported to star in an American film.” The star, Betty Nansen, is nothing short of “the greatest tragedienne in the world” and a “source of inspiration for the immortal Ibsen.”. 4

Yes, Betty Nansen is praised in superlatives by the men who carries her forward both in Denmark and over the pond. The Danish consul in New York even organises a reception for her and puts up a Christmas tree in her honour when she arrives at Christmas in 1914, bringing 45 suitcases with costumes worth more than $45,000, as the American gossip press writes. This is roughly $1.5 million in today’s money. The well-heeled Danish star, who allegedly feels at home in the company of kings, tsars and barons, who wears dresses of the purest gold and who has even inherited manuscripts from the world-famous Henrik Ibsen, is a rock-solid scoop for newsagents. 5

In the US, Fox invites the audience to experience “The Nansen Eye, The Nansen Tear, The Nansen Smile”, which might indicate that the Americans filmed Nansen’s facial expressions by way of close-ups. But since none of Nansen’s American films have survived, we can’t determine whether the Americans went any closer in their filming than they did in Valby at Nordisk Film.

Just like Asta Nielsen, Betty Nansen had large, expressive eyes, but in the Danish films that have survived, she seems – for a contemporary viewer who doesn’t hold their breath in awe that theatre’s great Nansen is now acting in films – a heavy and static posture. Not least if you compare her acting with that of Asta Nielsen, or for that matter, Clara Wieth. Like Axel Garde in the aforementioned quote, you must have experienced Nansen enthralling a theatre audience “only through the life of her face” to be carried away by her minimalist acting. The respectful distance from which the camera mainly films her doesn’t help either.

On the other hand, Betty Nansen corresponds better to the female ideal of the time than Asta Nielsen. Nielsen was often caricatured as thin and flat-chested, whereas Nansen was somewhat more voluptuous. But Nansen was also already in her 40s when she made her film debut, and maturity wasn’t – even then – an advantage for an actress, especially not in the US, where she soon faced competition from the somewhat younger stars.

Back to the theatre

The heavy load of cultural capital which Betty Nansen had brought with her from the theatre couldn’t be transferred to the film screen, judging by the audience’s preferences. Cinema-goers gave Nansen’s Danish films a pass, and Nordisk let her go when Fox came knocking and offered her an American career.

In the US, the rumour about Nansen had already spread, and her Danish films had received widespread positive publicity. However, Nansen didn’t really hit the mark as a film actress there either. She starred in five films in 1915, all of which received less of a mention in the American film magazines than their Danish predecessors.

Part of the explanation for the somewhat pauvre result of Nansen’s American adventure is that her first film for Fox Film Corporation ‘The Celebrated Scandal’ (1915) was marketed at the same time that the company had a megahit with actress Theda Bara. It would seem that the marketing department at Fox got so busy promoting the young steamy vamp Bara after her ‘A Fool There Was’ that the somewhat older Nansen with the somewhat more virtuous and high-culture profile was left to sail her own boat. In any case, Theda Bara’s film received more than ten times the exposure of Nansen’s film in American film magazines. 6

Although there were sky-high expectations for Betty Nansen as a film star in both Denmark and the US, success didn’t materialise on either side of the Atlantic. Financially, however, Nansen’s film career was a blockbuster success for her personally. She returned home to Copenhagen in 1915, and in 1917 she opened the doors to her very own Betty Nansen Theatre, which she bought for DKK 250,000. With this, she and France’s Sarah Bernhardt, who Nansen was often compared with, became pioneering women – the only two in Europe at the time to own a theatre in their own name. So if film as a genre was originally intended as a means of earning enough money to become an independent self-made woman, Betty Nansen made a success of it, even if her film career failed. And as for the theatre – it’s still there.

1. Garde, Axel (1913), “Betty Nansen”, In: Teatret: Illustreret Maanedsskrift for Teater og Skuespilkunst 12, 19 (August 1913), 146.

2. Sandfeld, Gunnar (1966), Den Stumme Scene, København, Nyt Nordisk Forlag, p. 206

3. Sandfeld, Gunnar (1966), Den Stumme Scene, København, Nyt Nordisk Forlag, p. 206

4. Read Vito Adriaensen’s article in Kosmorama (in Danish): 'The Nansen Eye, The Nansen Tear, The Nansen Smile' – Da teaterdivaen Betty Nansen gik til filmen. Kosmorama #283.

5. Read Alice A. Salamena’s article in Kosmorama: Money, Gossip and Devotion: Betty Nansen in the USA. Kosmorama #283.

6. Read Vito Adriaensen’s article in Kosmorama (in Danish): 'The Nansen Eye, The Nansen Tear, The Nansen Smile' – Da teaterdivaen Betty Nansen gik til filmen. Kosmorama #283.

Lars-Martin Sørensen, Head of Research Unit | 8 March 2023