Benjamin Christensen, the genius behind Häxan

Visual tricks, great visions and an incredible ability for self-staging. Film historian Casper Tybjerg tells the story of Benjamin Christensen, director behind ‘Häxan’ (English title: ‘Witchcraft through the Ages’) and Danish cinema’s first real auteur.

Casper Tybjerg, Film Historian | 6 December 2022

Today, Benjamin Christensen will be known to most people for his ‘Häxan’, which premiered in 1922 and is still a unique, surprising and fascinating film.

Made before the documentary was even invented, ‘Häxan’ uses a documentary frame crossed with a consistently sensuous portrayal of the superstitions of the past. The film is full of innovative technical tricks and special effects. Its images are firmly rooted in the mood and shaped by a distinct sense of the visual, while the director behind it, with a distinct touch of self-deprecating humour, turns himself into the main character to rather an unusual extent.

Even though ‘Häxan’is indisputably his greatest work, all the elements that characterised the masterpiece – technical innovation, sense for the visual, and self-staging – were repeated in the important, yet tumultuous career, he made for himself both before and after the film.

With a distinct touch of self-deprecating humour, Benjamin Christensen plays an incarnation of the devil himself in 'Häxan'. Film clip from 'Häxan' (Benjamin Christensen, 1922) © AB Svensk Filmindustri.

In the 1910s he established himself as a prominent figure in Danish silent films, even though (or perhaps precisely because) he only made very few films in comparison with his contemporaries. In the 1920s he carved for himself an international career: after ‘Häxan’, which in spite of its Danish cast was actually a Swedish production (editor’s note: so we unfortunately don’t have the rights to display it on our website), he worked first in Germany, and subsequently in Hollywood. Although the consolidation of Hollywood’s studio system in connection with the transition to sound motion pictures put an end to the American film career of the independent-thinking Christensen, he made a comeback in Denmark at the beginning of the 1940s, where he managed to make four more films.

Scandals, champagne and opera

Christensen was born in Viborg in 1879 as the youngest of twelve children. His family was wealthy enough to send him to university to study medicine. However, he dropped out of his studies to become an opera singer and was accepted at the Royal Danish Theatre’s school of acting, where he was in the same group as Clara Pontoppidan and Poul Reumert. Christensen debuted as an opera singer in 1902, but soon developed issues with his voice. He then tried out as an actor instead and was hired by the Aarhus Theatre, where he was praised by critics, not least for his talent in the art of using make-up, but where he also worked as a stage director.

However, in September 1906, he came into conflict with the theatre director and a number of fellow actors who felt that he was promoting himself to the press at the expense of others and the theatre. After a heated argument during a party organised for the actors, Christensen left the theatre in a furore: “Theatre Scandal in Aarhus”, wrote the capital’s newspaper Politiken. Christensen never returned to the stage and instead took over the agency for the French champagne company Lanson Père et Fils.

Long films and great expectations

On Christmas Day in 1912, the French epic film ‘Les Misérables’ was shown at the Odd Fellows Mansion in Copenhagen with the title ‘De ulykkelige’(which translates as ‘The Unfortunate Ones’, not ‘The Miserable Ones’, which is the common Danish title for Victor Hugo’s novel). The film was directed by the former master director Albert Capellani for SCAGL (Société cinématographique des auteurs et gens de lettres), a company that specialised in prestigious literary productions and was closely linked to Pathé frères, the world’s leading film company at the time.

‘Les Misérables’ was broadcast in four parts of approximately 40 minutes each (the last one was slightly longer), but in Copenhagen they were shown together, so the playing time lasted almost three hours. “Access to restaurant during recess”, the ads reassured, but this was an ambitious film screening of unprecedented duration. Some years later, Benjamin Christensen said: “For me personally, that film was a turning point. From that day on I knew that I wanted to be involved in such things.” (Vecko-Journalen, 09/02/1919).

Christensen had started his film career as an actor at Dania Bio Film, a newly formed company that had the same literary profile as SCAGL. The publisher Gyldendal had a significant financial interest in the company, which, from the outset, ventured internationally and printed posters with the film title in four or five languages. Although Christensen had stayed away from the stage since 1906, the newspapers presented his involvement as a string to the company’s bow: “Much is expected of Mr. Benjamin Christensen. As a film actor (character-producer) he is believed to have a great future ahead of him,” wrote the newspaper Riget (08/05/1913).

We might suspect that Christensen’s talent to butter up the press (as well as access to good champagne) may have played a role here, but in one of the company’s most talked about productions, the film adaptation of H.C. Andersen’ ‘Lille Klaus og store Klaus’(Little Claus and Big Claus), he played Big Claus. The film was made in June 1913. Soon afterwards, Christensen switched to another film company, Dansk Biograf-Kompagni, which had been started by the actor Carl Rosenbaum. Christensen played one of the main roles in the film ‘Skæbnebæltet’(which translates as ‘The Belt of Destiny’), which premiered in November 1913. A few weeks later, he assumed the position as the company’s director.

Sealed Orders

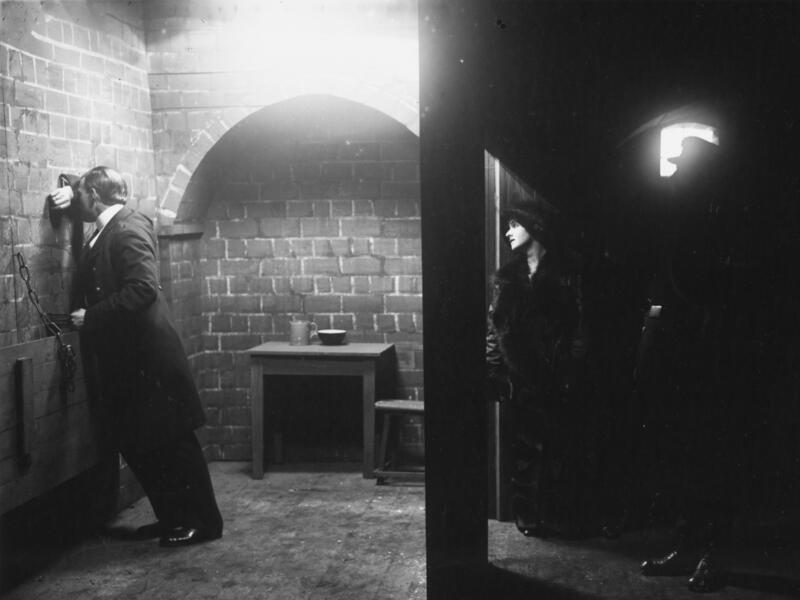

By this time, he was seemingly already hard at work shooting his first film as a director, Sealed Orders, which premiered in March 1914. The talent he displayed here convinced the investors that he was the right man to be at the helm. ‘Sealed Orders’ is a proper entertainment film, a spy melodrama, in which the male protagonist (played by Christensen himself) is a naval officer who, though innocent, is sentenced to death as a spy. He’s saved at the very last moment thanks to his wife and son, a big boy, who sneaks into the fortress where his father is imprisoned and delays the execution, while the wife crosses a battlefield during hostilities to find the real spy whose confession can save her husband.

‘Sealed Orders’ impresses not least with its many refined lighting effects. Several scenes are shot with a backlight (contre-jour), so that the figures appear as black silhouettes. In other scenes, the lights in a living room are turned on or off, which represented a significant technical challenge as sunlight was still the primary light source at the time. Other scenes have evocative and dramatic contrasts between light and shadow, such as the scene in which the boy sneaks into the fortress.

Without belittling Christensen’s originality and sense for combining the artistic sophistication of a film artist with dramatic and emotionally intense entertainment, it is worth pointing out that he was probably inspired by one of the best films of 1913, the French ‘L’enfant de Paris’(‘The Child of Paris’). This film, which had its Danish premiere on 4 August 1913, was directed by Léonce Perret for the film company Gaumont. Although the story is completely different, it has similarities with ‘Sealed Orders’, both in terms of a significant number of children’s roles and its refined lighting effects. In interviews many years later, Christensen himself recalled that he didn’t think that the films he starred in at Dania Bio Film and Dansk Biograf-Kompagni could measure up to Gaumont’s productions (Politiken, 26/03/1939).

A real auteur

Christensen’s next project, ‘Manden uden Ansigt’(which translates as ‘The Man Without A Face’), was shelved, most likely due to the outbreak of the First World War. After that, some time passed before he accomplished his next project, Blind Justice. Christensen himself said that after each film, each of which he worked on extremely hard, he got into the habit of taking long breaks, during which he could recover through “reading, having fun and traveling” (Politiken, 05/09/1926).

‘Blind Justice’ is a dramatic story about “Strong Henry”, played by Christensen himself, an escaped convict innocently convicted of murder, who seeks revenge on the woman he believes sent him back to prison. Christensen readily admitted that the character was inspired by Jean Valjean, the main character in ‘Les Misérables’ (Variety, 22/09/1916).

The film has even more visual refinements than ‘Sealed Orders’, including a scene in which the female protagonist locked herself away in fear of the escaped convict sneaking around in the dark. Suddenly the camera shows her terrified face, and then pulls backwards and out through a glass garden door, so that the bars are outlined as silhouettes – and then the dark outline of the burly convict appears in front of the door, which he easily forces open.

Also worth noting is the beginning of the film, where Christensen shows his female protagonist, Karen Sandberg (later Caspersen), a model of the villa where much of the film takes place. The light in the room is initially off, so their faces are only illuminated by a lamp inside the model. Before the film’s launch, the film company had been renamed Benjamin Christensen Film, and Christensen pointed out his own central role as a very dominant author of the promotional material for the film, where his face was seen in three versions: made up for the role of Strong Henry both as a young and as an old man, and then without make-up as the director.

In February 1919, Christensen was hired by the Swedish film company Svenska Biografteatern, whose eye for quality and high level of technical achievement he eagerly praised in the Danish press (København, 07/02/1919). He got rid of his champagne agency and bet everything on his career as a film-maker. In connection with this, he made a number of statements in which he expressed scepticism for the literary film adaptations for which Swedish film had been praised. Instead, he pleaded: “Let’s get film writers, or rather film artists, who write and stage their own films” (Svenska Dagbladet 02/03/1919).

Director and screenwriter must be one and the same person, argues Christensen, because films are made of images and must be thought through visually from the ground up: “I can’t free myself from the firm conviction […] that films must be made of images, which have been created precisely as images in a human brain and not as anything else, no matter what it might be” (Filmrevyn no. 1, 1919). He returns to this topic in his later interviews. In the near future, he states, we should “like to have reached the point where film director and film writer are no longer separate concepts, but are merged into one, for which we then have to find a name – in my language I want to call it an image-maker” (Svenska Dagbladet, 05/02/1920).

Witch with no hero and no action

At this point he had been preparing ‘Häxan’ for a year. In January 1920, Christensen tells a journalist that he is working on “a film from the Middle Ages”, but that he is still doing research (Klokken 5, 24/01/1920). At the Christmas of 1919, Svensk Biografteatern merged with another company to form the new giant company Svensk Filmindustri. The construction of SF’s studio in Råsunda was delayed, and in March it was reported that SF had bought Dansk Biograf-Kompagni’s old studio on Taffelbays Allé in Hellerup, where Christensen had shot both ‘Sealed Orders’ and ‘Blind Justice’. It took another year or so of preparations, including an expensive upgrade of the studio facilities in Hellerup, before filming of ‘Häxan’ could begin in February-March 1921.

Christensen’s project was shrouded in secrecy, but in May 1921 he was able to report that he was making “a cultural historical experiment in using living images” and that his goal was to make a “film with no hero and with no action”, which would “speak more to the viewer’s mind than their heart – striving for clarity rather than mood” (Berlingske Tidende, 23/05/1922). Although the concept of documentary film had not yet been invented, ‘Häxan’ was presented to be based on facts.

It begins as a lecture on the superstitions of the past: we see reproductions of book illustrations and details highlighted with a pointer. However, most of the film is made up of re-enactments, where scenes from the era of witch hunts are recreated using backdrops and actors.

By using a pointer, Benjamin Christensen explains a common belief in the Middle Ages: that devils lived in the core of the earth. © AB Svensk Filmindustri.

We follow a “typical” witch trial, where the people are named and the presentation is dramatic. However, the documentary ambition is quite clear: Christensen compiled an extensive bibliography of some 70 historical books which he had consulted in his research. Among the more bizarre manifestations of his desire for authenticity was his demand for the young Ib Schønberg (who plays a small part as one of the witch judges) to have one of his front teeth pulled out, so that his set of teeth in close-ups looked more authentically medieval.

However, what stands out with regard to ‘Häxan’ is the phantasmagoric wildness and tangibility used to recreate the belief in witchcraft. We see two old crones casting a curse by defecating in their respective night pots, spinning around, and kicking the pots towards the victim’s front door. Photographic effects and huge rotating landscape models are used to show hordes of witches flying through the air on broomsticks. We see witches kissing a devil’s backside, women nakedly embracing demonic lovers, and the preparation of witch’s brew – a scene in which a devil lets the fat of a roasted baby drip into the pot. ‘Häxan’ is characterised by great exaggeration.

The preparation of witches' brew. Film clip from 'Häxan' (Benjamin Christensen, 1922) © AB Svensk Filmindustri.

Under torture the old lady Anna Væverske (Anna the Weaver) names women who have been partying with devils and have been kissing their behinds. She also names neighbours who have been throwing around curses and night pots. Film clip from 'Häxan' (Benjamin Christensen, 1922) © AB Svensk Filmindustri.

The film is imbued with carnality, and Christensen’s explanation for the belief in witches is that it’s due to psychological delusions, which primarily stem from repressed sexual drive (it was a popular interpretation which was quite widespread in scientific circles of the day, although recent research has distanced itself from it). Yet the film’s ongoing sensuality created great difficulties for it outside of Sweden and Denmark, where it premiered in the fall of 1922. In Germany, it was premiered with a year’s delay, and in many other countries the film ended up being banned altogether.

Christensen himself has a distinct presence in the film: it begins with a close-up of the film-maker staring into the camera, his face shrouded in dramatic shadows. He repeatedly refers to himself as “I” in the intertitles, such as in a sequence where a young actress is testing a thumbscrew, and the director’s hand reaches into the frame and operates the instrument of torture. Christensen himself also appears as a satanic devilish figure with a tongue that makes monks recoil in horror and lures nuns into blasphemous madness.

Benjamin Christensen is present in many ways in 'Häxan'. Here the director's arm appears on screen, helping an actress trying out a thumbscrew. Film clip from 'Häxan' (Benjamin Christensen, 1922) © AB Svensk Filmindustri.

In these striking ways, he stages himself as the guiding force in the film. In a letter to Erik Nørgaard, dated 9 April 1953, Christensen wrote: “‘Häxan’ is and will be – throughout 30 years of directing – the only film I had the opportunity to produce exactly as I wanted, without any interference.” But for Svensk Filmindustri, which had given him free rein to make it, the film was a huge loss-maker.

From Berlin to Hollywood

Christensen had to continue his film career in Germany, where he directed two films, Seine Frau, die unbekannte (‘His Wife, the Unknown’, 1923) and ‘Die Frau mit dem Slechten Ruf’ (‘The Woman Who Did’, 1924). The latter has been lost and virtually no information is preserved about it. ‘His Wife, the Unknown’ is a strange, but in many ways charming film (to find out more about it, take a look at the Kosmorama article “Benjamin Christensen’s Wonderful Adventure”).

In Germany, Christensen also played a significant role as an actor: in Carl Th. Dreyer’s ‘Michael’ from 1924 (Danish title: ‘Mikaël’) he plays the aging painter Claude Zoret, called the Master, who nurtures a passionate affection for his young protégé Michael. In his thoughtless self-obsession, Michael inflicts one deep emotional wound after another on the older man until he eventually falls ill and dies. Christensen’s somewhat theatrical acting style suits the self-conscious and celebrated Master well, but he also manages to show his devoted love for the young man with great finesse and the helpless pain that the repeated failures add to the character.

In 1923, probably the most famous and most admired European film-maker of the time, the German Ernst Lubitsch, went to Hollywood to make films there. He was soon followed by a whole host of European directors, including Christensen, who was hired by the newly established major corporation MGM. There he made two films: a circus drama, The Devil’s Circus (1926), and a period drama about the Russian Revolution, ‘Mockery’ (1927). ‘The Devil’s Circus’ is centred around the image of a grim, devilish figure pulling the strings of fate. The film is full of dramatic events: an act of rape, a debilitating fall from the circus dome into the lion cage, and a miraculous recovery.

We notice that this is a relatively conveyor belt-like production. The year before, MGM had success with another circus drama, the Swedish master director Victor Sjöström’s ‘He Who Gets Slapped’, in which Norma Shearer, who also plays the lead role in ‘The Devil’s Circus’, had her own breakthrough. Shearer’s biographer Lawrence Quirk states (using a conversation with director King Vidor as his source) that Christensen was quite close with her until she complained to the studio manager Irving Thalberg, with whom she was in love and married in 1927 (Quirk 1988, 77). Although the illustrator Christensen does appear in some scenes, such as in some dizzying positions from the circus dome, both ‘The Devil’s Circus’ and ‘Mockery’ lack his personal touch.

On the other hand, these can be found in Christensen’s last preserved American film, ‘Seven Footprints to Satan’. In 1928, Christensen had moved to the film company First National, where he made four films in quick succession, three of which have unfortunately been lost. ‘The Hawk’s Nest’ (1928), ‘The Haunted House’ (1929) and ‘House of Horror’ (1929). All three seem to have been fast-paced entertainment films with lots of thrill, creepiness, secret passages and, in the case of the last two, a good dose of humour and comedy. ‘Seven Footprints to Satan’ is also a horror comedy. It is loosely based on a novel by Abraham Merritt, an important pioneer of horror and fantasy literature.

Merritt’s book is an intense and grim thriller about a young adventurer and fortune-seeker who falls into the clutches of a mysterious supervillain, a sadistic criminal genius who calls himself Satan. The hero is imprisoned in Satan’s fortress outside New York and is forced to commit crimes at his behest. In Christensen’s version, he is an otherworldly but wealthy geek who gets it into his head to travel to distant lands and experience dangerous adventures. The abduction, the sinister Satan, the gloomy labyrinthine fortress full of ill-fated and macabre figures – everything is arranged by the main character’s uncle to emphatically rid him of any desire for adventure.

It is all actually staged, but that only gets revealed towards the end. The film speeds along at a frantic pace as our hero and his beautiful sweetheart run around the mysterious house filled with secret doors, hooded servants, orgies, a dwarf, a gorilla, and many more strange things. The American film researcher Arne Lunde has deftly interpreted this entertaining horror comedy as Christensen’s satire of the American film production environment, where he himself is “both the naive and bewildered comic protagonist and the all-knowing, all-controlling master architect behind the narrative’s play with stunts and conjuring tricks” (Lunde 2010, 18). The transition to sound motion pictures and the onset of the Great Depression led to a consolidation of the American film industry which made conditions extremely difficult for smaller independent production companies. Christensen tried to start an independent company together with his friend, the film journalist Wid Gunning, but they failed, and in 1935 the director Christensen returned to Denmark.

The image-maker’s exit

In 1939, the last stage of Christensen’s film career began with four films for Nordisk: ‘Skilsmissens Børn’ (‘Children of Divorce’, 1939), ‘Barnet’ (‘The Child’, 1940), ‘Gaa med mig hjem’ (‘Come Home With Me’, 1941), and ‘Damen med de lyse Handsker’ (‘Lady with the Light Gloves’, 1942).

The first three are relatively serious everyday dramas. ‘Children of Divorce’ describes a generation of self-obsessed parents whose irresponsible behaviour has harmful effects on their teenage children. ‘The Child’ is about two young people who have to deal with the consequences of an unwanted pregnancy and are forced to consider an illegal abortion. ‘Come Home With Me’ is an ensemble film dominated by Bodil Ipsen in the role of an idealistic lawyer who has taken in a number of troubled people to live with her until they get back on their feet.

Christensen received praise from critics and was a success with audiences for his relatively realistic portrayals and sensitive character direction. His last Danish film, ‘Lady with the Light Gloves’ was, however, a resounding failure. The film was a spy melodrama, which attempted to recreate the type of loud entertainment that he started his film career with in ‘Sealed Orders’ and had success with at First National. We can sense the outline of the same type of self-parody which Christensen successfully brought to fruition in ‘Seven Footprints to Satan’, but in ‘Lady with the Light Gloves’ the effect just falls completely flat. The story has a manipulative master figure, “His Excellency”, but it lacks weight, and the absurdly complicated and unreasonable plot doesn’t seem playfully self-deprecating, but merely slow and clumsy.

It was a project that Christensen himself had been eager to do. A journalist who had spoken to him writes that people at Nordisk had been “sceptical” about the project, “but the director was keen to pursue his idea – and people yielded because if such an experienced man as Benjamin Christensen was so confident about producing a spy drama, one didn’t dare to doubt him” (Socialdemokraten, 05/08/1942).

That was the end of Christensen’s career as an image-maker. He received a grant for the cinema Rio Bio in Rødovre, which he ran until his death in 1959. When he celebrated milestone birthdays, he gave interviews in which he retold well-known anecdotes, but where he had once eagerly sought the attention of the press and staged himself as the demonic master of shadow images, he now guarded his privacy and preferred to live in obscurity.

Literature:

Jensen, Jytte, editor. (1999). Benjamin Christensen: An International Dane. New York, Danish Wave ‘99 / Museum of Modern Art.

Lunde, Arne (2010). “Scandinavian Auteur as Chameleon: How Benjamin Christensen Reinvented Himself in Hollywood, 1925–29.” Journal of Scandinavian Cinema 1 (1): (7-23).

Quirk, Lawrence J. (1988). Norma: The Story of Norma Shearer. New York, St. Martin’s Press.

Tybjerg, Casper (2019). “The Spy who Loved Me: Benjamin Christensen and the Danish Silent Spy Melodrama.” Journal of Scandinavian Cinema 9 (3): (253-276).

Tybjerg, Casper (2020). “Benjamin Christensens vidunderlige eventyr: filmhistorie og ‘Practitioner’s Agency’.” Kosmorama #276.

Casper Tybjerg, Film Historian | 6 December 2022

Watch the films

Behind the scenes

Unique behind the scenes recordings from Benjamin Christensen’s films and from cinematographer Johan Ankerstjerne’s archives.

Casting: These casting recordings are presumably from 'Häxan' and Benjamin Christensen's 'Helgeninderne' (female saints), a never finished film that he shot simultaneously. Christensen casted both professional and unknown actors for 'Häxan'. He was very meticulous when it came to choosing the right people for the roles and often demanded a lot (maybe too much) from his actors. In these recordings, for instance, Benjamin Christensen grabs an actress's breasts. We haven't been able to identify all the actors in the recordings, but the last one is definitely Alice O'Fredericks, who plays a nun in 'Häxan'. .

Special effects. Benjamin Christensen's films were often expensive and time consuming, because (amongst other things) he loved taking his time experimenting and making technical innovations. First up, in these recordings, we see him experimenting with double exposure with himself in front of the camera as a preparation for the scene in 'Häxan', where flocks of witches fly through the air on their way to the Brocken. Next up, we see different text material from 'Sealed Orders', that was shot in different versions for different countries. The last recording is shot on a set piece resembled an old tree building. A woman is standing in the foreground, looking up a flight of stairs, while Benjamin Christensen (dressed in a worker's costume) is seen looking at her from the background..

Related articles

Silent Film Festival in Copenhagen

If you come to Copenhagen in January, you can watch silent films at the silent film festival in The Cinematheque. Benjamin Christensen is this year’s headliner. The cinema will be screening ‘Blind Justice’ (1916), ‘The Devil’s Circus’ (1926) as well as Carl Th. Dreyer’s ‘Heart’s Desire’ (‘Michael') (1924), where Benjamin Christensen plays a leading role.

The program is in Danish, so please contact sarapr@dfi.dk if you need information about the festival in English.