Infatuation, Writing, and Self-Irony

Danish silent cinema and Danish film actors achieved fame across the globe. The most dedicated members of the audience developed the first film fan cultures: enthusiastic cinema-goers who never missed a single film starring their idol, avid collectors of memorabilia, tireless readers of the press in search of personal information about their star, and writers of letters—lots of letters—which today provide insight into what motivated the greatest fans of silent film stars.

Stephan Michael Schröder | 15 January 2025

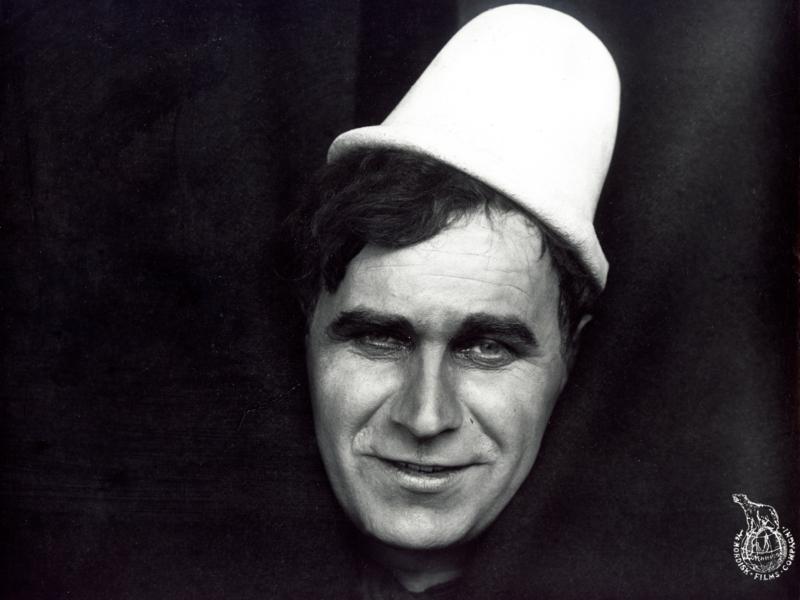

Film stars are stars not least because of their fan bases, and fans would not be fans without idols. Nevertheless, the relationship between the two quickly proved to be quite conflict-ridden as the first film fan cultures emerged around 1910. For the stars, it was of course flattering to be admired by so many people. But admirers also demanded to be noticed. They wanted to know everything about the stars and, ideally, to meet them in real life. When Asta Nielsen celebrated the opening of a new cinema, when Valdemar Psilander visited Budapest in 1914, or when the American stars Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks met their Danish fans while passing through Copenhagen in 1924, crowds filled the streets. When the comedy duo Carl Schenstrøm and Harald Madsen, known as Pat and Patachon, visited Hamburg in January 1931 at the height of their international film careers, 20,000 fans welcomed them, reported Danish daily Politiken on 11 January 1931.

“Pat” recounts the reception in Hamburg in 1931:1

In Hamburg, as we got off the train, we were surrounded by many thousands of people; we were separated from one another. People screamed with delight. Small children screamed because they were being crushed. We shuffled along because we could not lift our legs. We were literally packed like sardines in a barrel. […] Eventually we reached open air, but it did not get any better. I had to shuffle forward—I saw a bicycle leaning against a lamppost—I wanted to avoid it, and of course I was led straight toward it. I got my leg caught in the spokes of the bicycle—could not get free—fell flat because my leg was stuck. People moved over me. I had to scream: “Help.” I am endowed with a fairly powerful voice. Still, it took some time before the police could clear the way and carry my abused and trampled body over the heads of the crowd to safety.

And Schenstrøm adds ironically: “I do not care for freedom of the press in that form.” 2

The Connection Between Fan and Star

Personal encounters between fan and star were, however, the exception. Within a few years, writing fan letters became one of the most important fan activities. Clara Wieth (later Pontoppidan) fondly recalled the fan mail she received in her memoirs:

Oh, what exciting letters and billets-doux one received, praising one’s blondness and Nordic sensibility. […] Praise, letters, goodwill poured in for Carlo and me from literally all corners of the world. 3

On some of the envelopes Wieth kept from such fan letters, she noted the respective countries of origin. In this way, they illustrated her worldwide fame (and this is probably the reason they were preserved), from countries such as “Bosnia,” “Japan,” “Russia,” or even “Bavaria.”

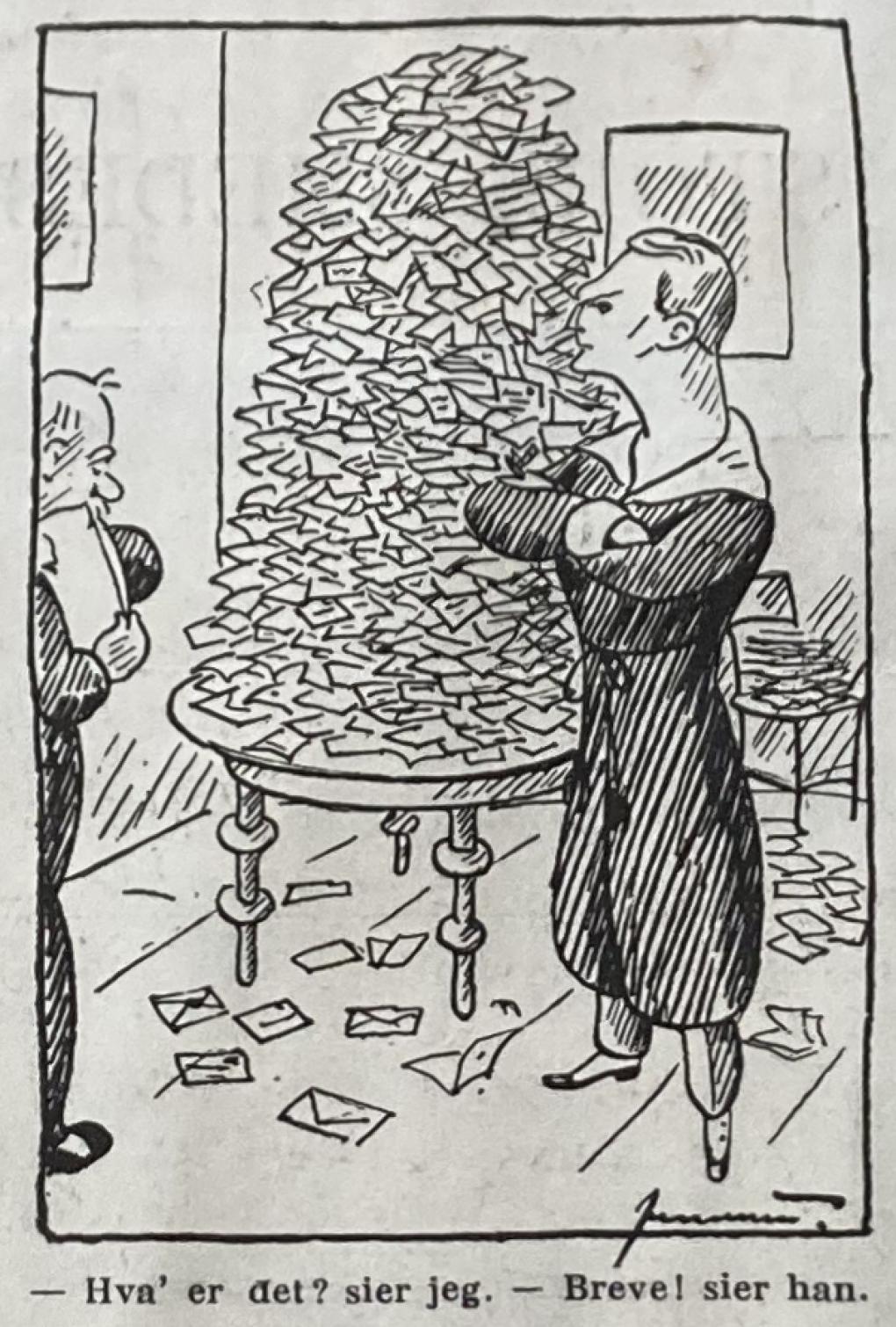

Yet Clara Wieth’s memory of fan letters may have become somewhat rose-tinted over time. Contemporary testimonies from the 1910s and 1920s often emphasized what a burden masses of fan letters represented. In the United States, people even spoke of a “letter writing lunacy” that film stars had to deal with in one way or another. The phenomenon was so widespread that caricatures of being inundated with fan mail were also drawn in Denmark. 4

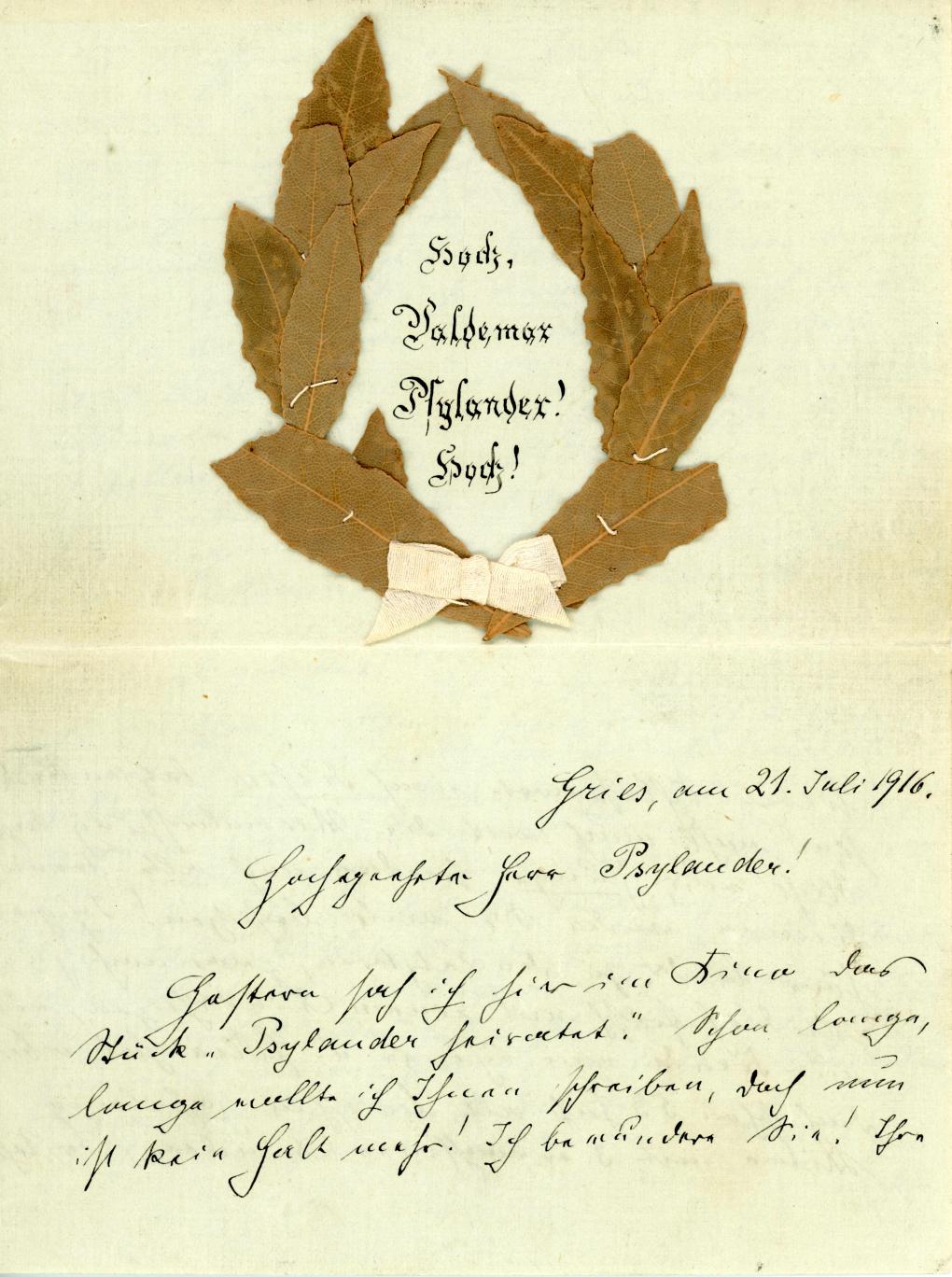

Valdemar Psilander, the Danish silent film superstar, was known for neither reading nor answering his many fan letters. In the newspaper København, he candidly admitted on 4 March 1913:

At the cinema and in my home there are piles every day […] I receive approximately a thousand letters a year from all parts of the world requesting photographs or autographs, with invitations for pleasure trips in the company of the female letter-writer […] I receive letters in Russian and Chinese […] My wife reads them all […] it is her favorite novel reading.

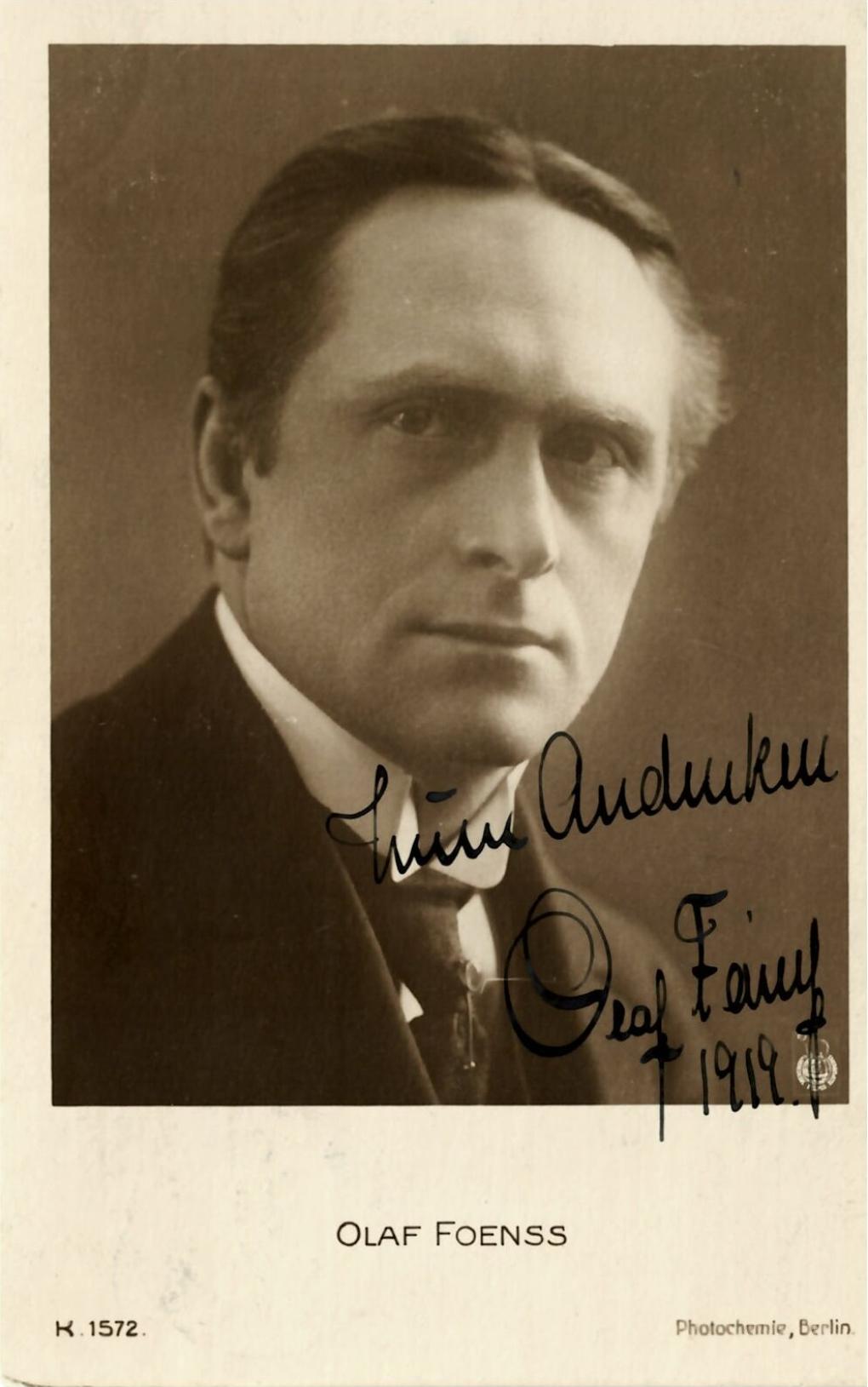

How literally one should take the figure of a thousand letters a year remains somewhat unclear—but there were undoubtedly numerous letters that went unanswered. Psilander’s colleague Olaf Fønss chose a typical compromise of the time: he sent signed portrait postcards in response. In his memoirs, however, he revealed that it was often not he himself who affixed the signature to the cards:

[T]wo ladies in the office were assigned to answer [the daily stack of letters] by imitating my handwriting as well as possible and putting my name on postcards to all admirers, male or female. 5

Asta Nielsen acted in exactly the same way, entrusting the daily fan mail to her secretary, “who had practiced writing my name and thus kept all parties unharmed.” 6

Nevertheless, film fans continued unabated to send letters and postcards by the thousands, asking for autographs or a personal reply—presumably in the hope that their letter would be the exception to the rule. In letters after 1914, it is striking how often secretaries are mentioned and requests are made for a personal signature—a phrasing that reflects public knowledge of forged autographs. And even though one knew how great a task it was for film stars to handle their fan mail, disappointment often set in if the reply did not come as desired. For example, Annie Berger from Vienna became truly angry in 1920:

Olaf Fønss! Today I received a card from you which, instead of making me happy as you surely believe, makes me deeply sad. I have written three letters to you and receive in reply a card with the words “in remembrance.” That is bitterly little. How much you have misunderstood my letters. Or rather, what I believe, not read them at all. Perhaps you carelessly threw them into the fire and deprived me of a hope. You are right, of course. What concern is it of yours what a woman you have never seen has to say.

Fans of Danish Silent Film Stars Around the World

Although Danish silent film stars had fans all over the world, they are largely undocumented in Danish film history. There is also little documentation of international fan cultures from the silent film era. The thousands of fan letters sent to stars were usually thrown away. What has been preserved was either saved by chance or selected by the stars themselves as examples of particularly exotic or eccentric letters. The collections are therefore anything but representative. In the two largest known collections outside Denmark—the fan letters to the French actor René Navarre in Paris and the collection of the American Florence Lawrence in Los Angeles—239 and 108 letters from the silent film era have been preserved, clearly only a fraction of the letters the two stars must have received.

When it comes to Danish film stars, the situation looks slightly brighter: 168 letters from the silent film years to Clara Wieth, 131 to Asta Nielsen, 48 to Betty Nansen, a few original letters to Carlo Wieth, Valdemar Psilander, Aage Fønss, and Emilie Sannom, plus printed reproductions of letters to Pat and Patachon 7. It would have been wonderful to have preserved fan letters to actors such as Robert Dinesen, Ebba Thomsen, or Gunnar Tolnæs—perhaps piles still lie in some attic somewhere?

What is unique about the situation in Denmark, however, is that the Danish Film Institute holds the world’s largest collection of fan letters to a popular silent film star, which is not only ten times larger than the next largest collection, but also complete. The fan letter collection of Olaf Fønss comprises a total of 2,257 letters, postcards, and visiting cards from the period 1913–1929. Fønss was not only a major star; he was also a vain man who collected everything written about him and to him—otherwise this exceptional collection would not exist.

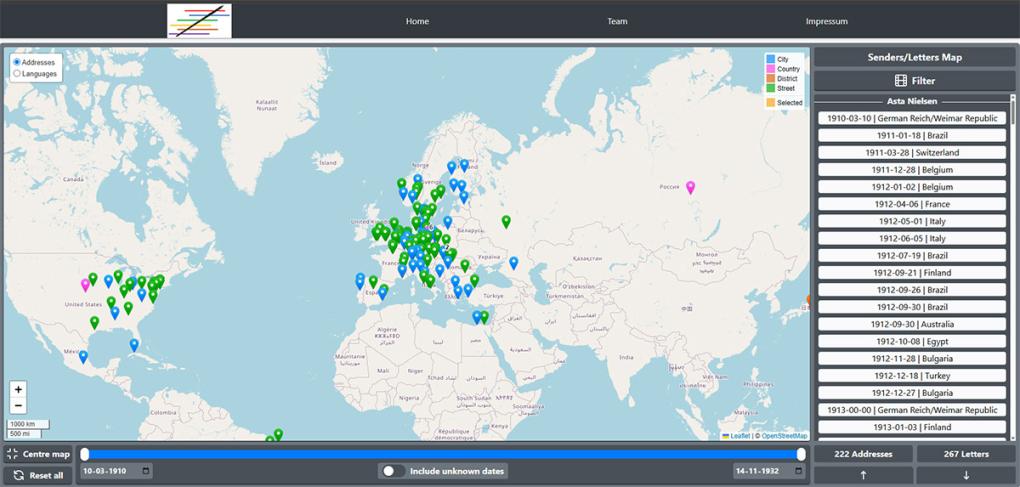

The archived letters to Danish film stars clearly illustrate their international reach. Fans write from all corners of the world, from Japan to Brazil. In an ongoing research project at the University of Cologne, we are currently placing all letters with sender information on a world map in order to convey their geographical spread visually.

Map of fan letters to Danish silent film stars

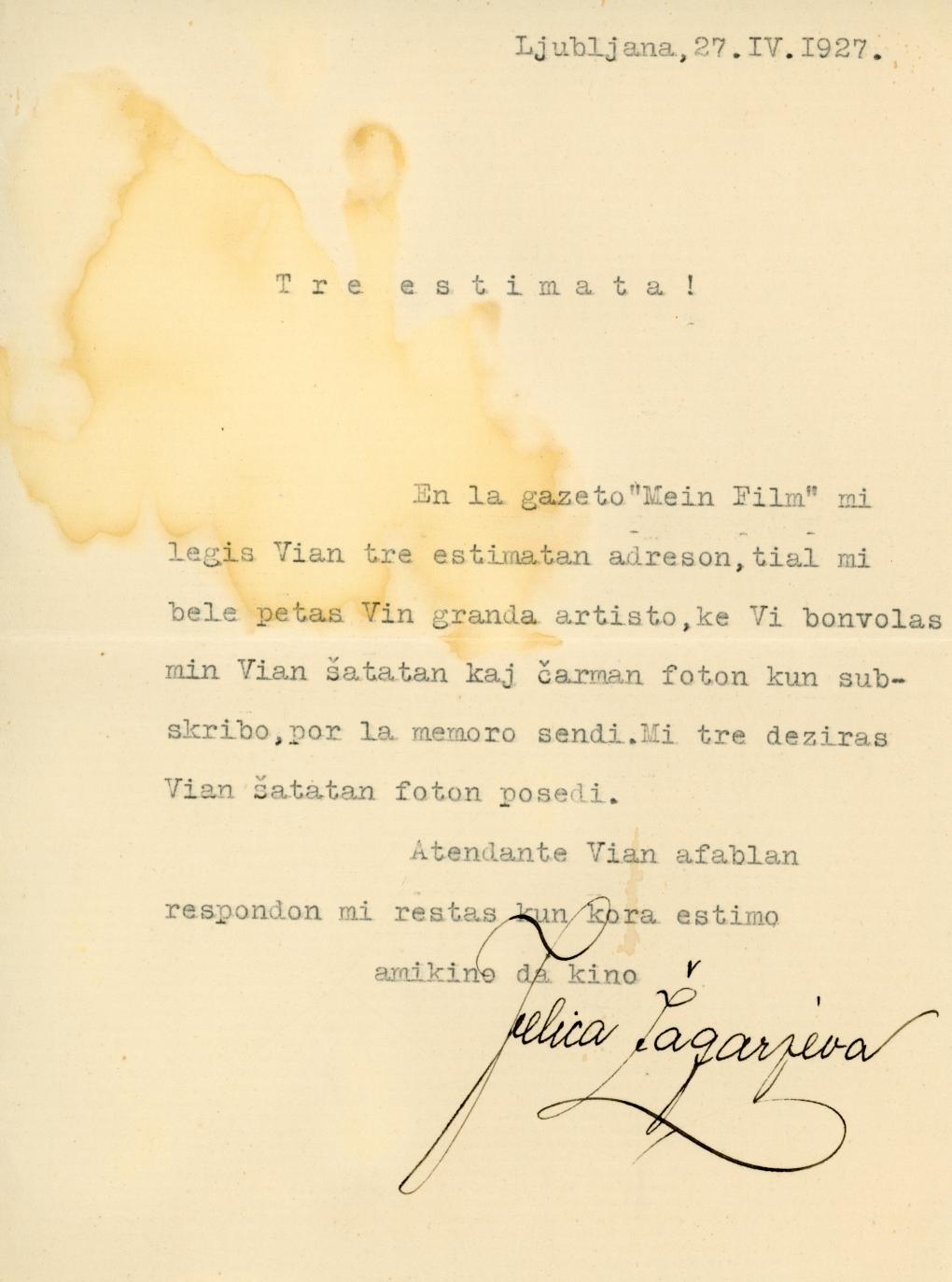

The letters come in all kinds of languages. These include, of course, the Nordic languages and the linguae francae of the time (above all German), but also more exotic languages such as Estonian, Romanian, Russian, or Hungarian. And in a language that virtually symbolizes internationalism itself: Esperanto.

Fans Speak Out

Among the more than 2,600 preserved letters to Danish silent film stars are marriage proposals, autograph requests, appeals for help entering the film industry, self-written screenplays, spontaneous outbursts of enthusiasm about a film just seen at the cinema, questions concerning the interpretation of what was seen, self-written poems or songs, and requests for advice on how to live. While the press liked to give the impression that fans were pubescent girls from the lower classes, the fan letters reveal how broad the fan base actually was. There is a plea written on a countess’s fine stationery embossed with a golden crown, alongside pencil-scribbled lines full of spelling errors on the cheapest paper. Young girls and women are strongly represented, but they are by no means the only ones who write. Some limit themselves to a single inquiry; others send dozens of letters over the years. Some fans are devoted to a single star, others are attracted to celebrities in general. Carefully composed personal letters coexist with copied template texts that fans could obtain from publications such as Mein Film-Buch, an annually published manual for fans in the German-speaking world during the 1920s. It provided exemplary letter texts in four languages (German, English, French, Italian) for those who could not or did not dare to formulate their own, or who were simply too lazy to do so.

Many letter writers, however, were not at all satisfied with pre-printed content in their letters. Instead, fans attempted to create a reciprocal relationship by sending the star personal memorabilia, such as photographs of themselves, pressed flowers, locks of hair, poems, paintings and drawings, or hand-knitted clothing in the hope that the star would wear it. Many of these items mentioned in the letters have unfortunately been lost, apart from numerous enclosed photographs and a few drawings.

It is striking how many fans reflect on their own role as fans, among other things by ironizing about themselves. Others surrender completely to infatuation. And some combine irony and infatuation. A good example is the letter that Pipsy Kecerin wrote to Olaf Fønss:

Written on 1 December 1916 at 9 p.m.

Oh! Only one, beloved Homunculus!

…… Fortune was so kind to me and allowed me to see your divine person also in this role ……

Since that day—three years ago—when I was first allowed to admire you, I have found no peace. Your spiritual features, which I love so dearly and of which I cannot get enough, every single one of your movements, your noble appearance, do not leave me; neither by day nor by night. Your soulful, deep gaze penetrates my soul like a warm, golden ray of spring sunshine. — — “Oh, stay here, glorious sun, grant me your light—your warmth! Do you smile? — Do you smile at a little Croatian girl who loves you indescribably much? — Oh, please, please do not do that, it hurts so much!” —

If my beloved artist has a moment to spare, I beg him with all my heart to remember his glowing admirer,

Pipsy.

P.S. I was ill for three days and was not allowed to leave my bed. This afternoon I was told that my beloved artist plays “Homunculus” in his latest role; I jumped out of bed (with a fever of 38 degrees), went to the cinema, and now I believe I am completely well.

Isn’t that sweet?

The semi-religious undertones are unmistakable: Olaf Fønss healed her by appearing as Homunculus on the screen. Or should we read the end of the letter as a small ironic reflection on her infatuation?

In fact, there are surprisingly many examples in the letters—above all from young women—that suggest a rather self-aware positioning of themselves at the intersection of their own enthusiasm and the media’s critical image of fans. Being a fan meant seizing the opportunity to break with the narrow conventions of the time. Numerous contributions consciously emphasize awareness of breaking norms by writing, often accompanied by gentle self-irony about one’s own position as a fan. To conclude, a few of these fans shall speak for themselves:

Until now, I have not found a person who understood me and completely shared my views. My father is a lawyer and therefore probably so very prosaic, my mother is from a very aristocratic family and does not consider many nice people as "befitting our status". I can't understand that at all. […] Nobody here understands that I much prefer to go to the theater or cinema than to dance at balls with silly and boring lieutenants, because most of the time they are. In reality, I don't know why I am writing all this to you.

(Erna von Dassel, 18 years old, from Hamburg, 1914)

Dear Sir! We are a clique of girls aged between 15 and 26. Please forgive me for not telling you which category I belong to, but rest assured that I am not the oldest, nor the youngest, but definitely the craziest of them all. […] Now, for once, we are studying the cinema program in a bellicose mood: Homunkulus with the famous Olaf Fönss. We are not exactly suffragettes or sworn enemies of marriage, but we don't think much of men. […] I don't think I should continue writing my letter. Why should I help to increase your vanity, which has probably already grown to gigantic proportions? […] Why should I bother to say any more: we are head over heels in love, all five os us. With you. That is, with the Olaf Fönss we see. Now and then, one of us is cruel enough to tear the dreams of the others to shreds with their bare fists: »He's probably 55 years old and has a wife and fourteen children. He walks around in a dirty dressing gown and slippers with worn-down heels before he puts on the ›handsome man‹.« – But she doesn't believe it herself and almost begs for the vile suspicion to be taken back, almost in tears. And we love you all again with the same fervor as before.

(Anonymous, from Kapfenberg/Austria, 1917)

We decided that since we can't meet you in person and see you so rarely in the cinema, we would at least admire you on the photo, which we would hold in indescribable honor.. […] My little god! If our mothers knew about this, we'd probably be grounded for a week and they wouldn't take us to the movies anymore, and that's why we put the address below as the sender, because nobody knows about it. We ask very nicely, do not blame us for that! It is true that we are also ashamed, it may be that we do not behave properly, but sweet little God, what does it matter that we ask for a photo from an actor who lives so far away.

(Csöby Keresztény and Idus Réthy from Miskolc/Hungary, 1917)

Much more about silent film fan cultures can be explored on the website fanmail1910s.de, which presents the research project “Fan Mail to Danish Film Stars in the 1910s: Exploring the Agency and Practices of Early Film Fans.” Here, selected letters are available in the original language and in English translation, along with graphs and contemporary texts on fan culture in Denmark and other countries.

Notes

1. See also Jannie Dahl Astrup: Fy og Bi: Et transnationalt filmfænomen. En undersøgelse af grænsekrydsende entanglements i produktions-, distributions- og modtagerperspektiv. Ph.d.-afhandling. København: Københavns universitet, 2022, 158ff.

2. Carl Schenstrøm: Fyrtaarnet fortæller. København: Hagerup, 1943, 131f.

3. Clara Pontoppidan: Eet liv – mange liv. Første halvdel: Til 1925. København: Steen Hasselbalch, 1965 [1949/50], 210, 218.

4. See https://www.uni-koeln.de/phil-fak/nordisch/fanmail/Carter%20Letter-Writing%20Lunacy%201920.pdf

5. Olaf Fønss: Krig, Sult og Film. Films-Erindringer gennem 20 Aar. II. Bind. København: Alf. Nielsen, 1932, 116.

6. Asta Nielsen: Den tiende muse. Vol. 2: Filmen. København: Gyldendal, 1946, 53.

7. See Robert Eddy: Fyrtaarnet og Bivognen. Biografi – Bedrifter – Berømmelse. København: Zinklar Zinglersen & Co., 1928, 101–112.

Selected films starring...