Nordisk Goes Big in the Year of the Comet

A fascinating, fresh, and ambitious film. Its visual design, cinematography, lighting, and special effects are far more polished than most of what’s on display in D.W. Griffith’s “Intolerance”. Gripping entertainment and a vivid introduction to storytelling strategies characteristic of Danish silent cinema. David Bordwell heaps praise upon the 1916 apocalyptic disaster movie “The End of the World” in this article; a detailed style analysis of director August Blom’s monumental film.

David Bordwell, Professor Emeritus | 22 April 2021

Was there any aspect of cinema not invented in the 1910s? I’ve argued that the period 1908-1920 is the foundation stone of our modern storytelling cinema.1 Even the genres we know — the Western, the romantic comedy, the gangster film, the melodrama — emerged then, in America and other film-producing nations. But what about movies that seem much of our moment? There are, for instance, those cosmic disaster movies like Independence Day (1996), Armageddon (1998), 2012 (2012), and San Andreas (2015),not to mention the Godzilla franchise. The genre received a more abstract and philosophical makeover by the Dane Lars von Trier in his provocative Melancholia (2011).

We might be tempted to see these projects as reflecting our current anxieties about our future. But such concerns are hardly unique to us. Humanity’s ultimate cataclysm has been a tempting subject for storytellers over the years. In 1916, the esteemed Nordisk Films Company gave us a prototype of how film could treat the apocalypse. The title sums up the threat looming behind the grandiose blockbusters of today: The End of the World (August Blom, 1916).

This very ambitious production sets in place many of the conventions of the genre. We’re subjected to suspense as the disaster approaches, and we watch the differing responses of people to imminent doom. We see science try to cope with something not fully understood and apparently uncontrollable. We’re also rewarded with the possibility of survivors rebuilding a new world. Just as important, The End of the World is a fascinating film in its own right, both gripping entertainment and a vivid introduction to storytelling strategies characteristic of Danish silent cinema.

Apocalypse in town and country

The need to make this big movie was born, most historians agree, in response to Nordisk’s strength in world film commerce. The early years of the Great War were good to the firm, because Denmark’s neutrality allowed films to be distributed in markets on both sides of the hostilities. Nordisk expanded production, hitting a peak output in 1915, the year in which The End of the World was made.2

Companies in France and Italy were making longer and more splendid films, so in order to compete Nordisk began mounting productions running longer than the usual three reels. The End of the World, at six reels, was the second-longest film released by Nordisk in 1916.3 The director, August Blom, gained international fame for another spectacular, Atlantis (1913), and he seems to have been Nordisk’s go-to master of grandiose spectacle. There he presented a version of the sinking of the Titanic; here the canvas is much wider.

The length and scale demanded a plot of quasi-novelistic complexity. Like a modern disaster film, The End of the World weaves the fates of individuals into the broader spectacle. In a mining village, foreman West has two daughters. Dina attracts the attentions of the surly miner Flint, while Edith agrees to marry the young sailor Reymers. The couples’ lives are disrupted by the mine owner Frank Stoll, who falls in love with Dina at a village dance and elopes with her. Dina becomes Stoll’s wife and lives in luxury in the city. Meanwhile, Reymers has signed on as first mate on a sea voyage and leaves Edith waiting. Flint nurses his grudge against Stoll. West and his friend, the itinerant Preacher. look on helplessly.

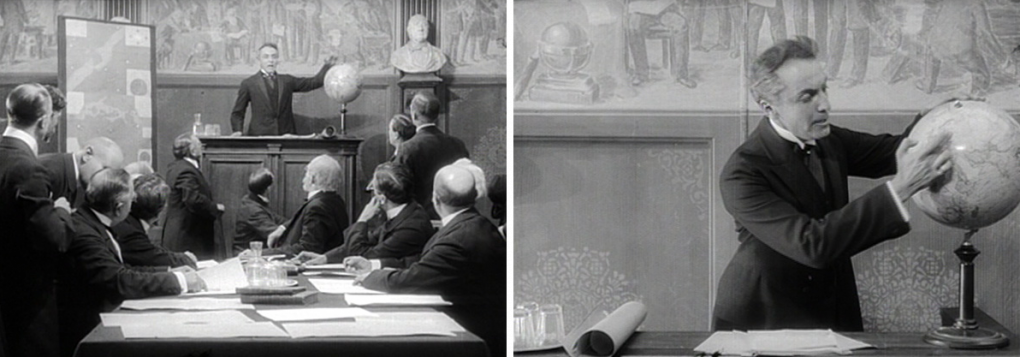

How to connect the domestic intrigues with a crisis on a global scale? One solution, seen in modern apocalypse plots, is to bring in a scientist. The astronomer Professor Wissmann has discovered that a comet is going to collide with Earth on 20 September. Wissman’s cousin is Stoll, who has learned the truth and schemes to use the impending catastrophe to conquer the stock market. In addition, by sending Reymers to sea the film’s plot can show the vast spread of the disaster, which triggers tidal waves.

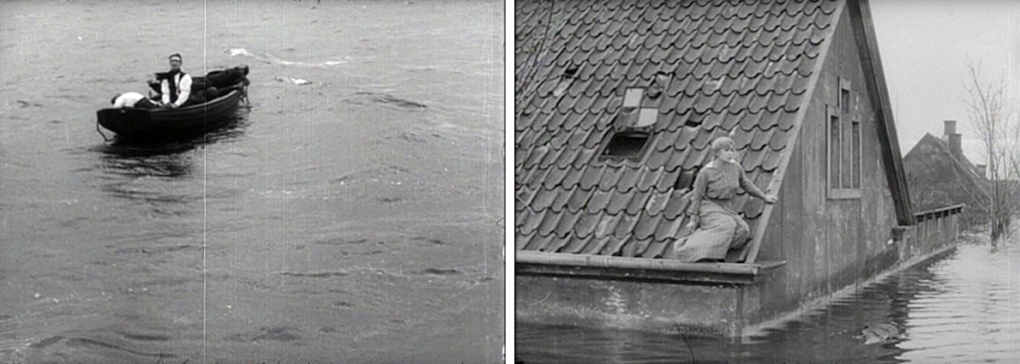

Stoll and Dina return to the village, where their presence causes old West to die of frustration and shame. On the fateful night, the comet strikes. While the Preacher leads the villagers in prayer, Stoll hosts a banquet celebrating his financial triumph and the victory of his class. But the vengeful Flint leads the miners in an attack on Stoll’s mansion. Stoll, Dina, and Flint die in a secret tunnel. As the earth burns and the seas rise, Edith and the Preacher manage to escape. Sheltering in an abandoned church, Edith tolls the bell, and Reymers, who has been cast ashore, hears her call. The lovers are reunited and kneel in humility and thanks.

Historians have been inclined to lump the film into a cycle of wartime Nordisk superproductions aiming capture international attention. These have been considered clumsy efforts to win all sides with a moralizing message preaching bland peace and brotherhood. 4 Coming after the crisp urban melodramas and crime films that made earlier Nordisk films popular worldwide, projects like The End of the World seemed to signal pretentious bloat.5

Today, though, the film looks fresh and ambitious. Its visual design, cinematography, lighting, and special effects are far more polished than most of what’s on display in Intolerance, released in the fall of the same year. Reviewers in the American trade press praised the Danish release highly, particularly for its handling of spectacle.6 Not least, I think, Blom’s film represents a rewarding effort to stretch qualities of Danish filmmaking style to suit storytelling on a colossal canvas.

Scaling up

To go big, The End of the World flaunts what we would now call production values — signs of care and money lavished on staggering imagery. The most apparent instance can be seen in the big sets. The mining village itself, filmed from afar, constitutes the major location, and Blom makes good use of the landscape for extreme long-shots. The interiors are no less impressive, from the Stock Exchange hall to Stoll’s extraordinary mansion, with its vast banquet hall and even bigger salon, where a “Star Ballet” is conducted to entertain the decadent rich. Most memorable is the exterior set of the sunken village, seen after the deluge.

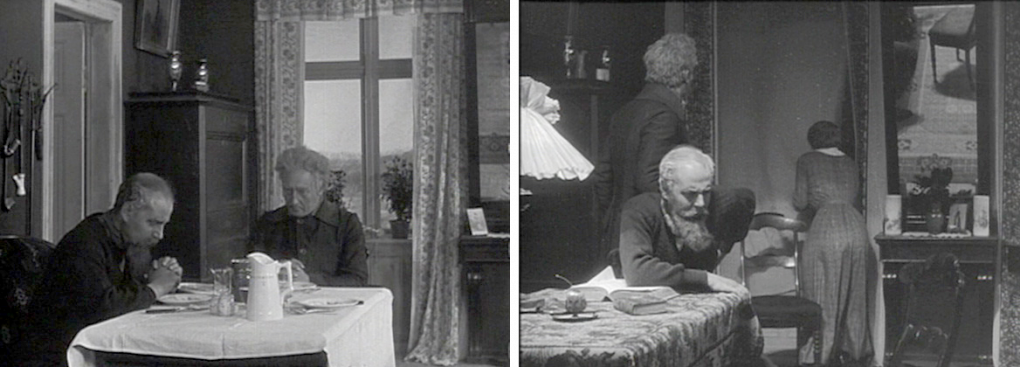

Not that all the sets are grand. The End of the World judiciously sets alongside its big spaces the humble home of the West family. It has a mirror tucked into the upper right corner of the frame, but that isn’t as prominent as it would have been in the elaborate staging of the early 1910s. And the parlor window, while notable, doesn’t look out onto a vista, as it might in another Danish film. Instead, the window contributes to the suspenseful finale, when during the comet’s assault water floods into the cottage.

The window also furnishes an important motif for the action to come.

A viewer today is likely to be struck by the film’s ambitious special effects. The comet’s approach is shown at intervals as a glowing speck in the sky, getting bigger in the course of the action. Even more impressive is the very big model of the village, built on a slant to permit a steep high angle. A production still shows its scale, with apparently director Holger-Madsen (perhaps visiting the set?) stooping in front. This very plausible mockup will be subjected to a meteor shower when the comet finally hits.

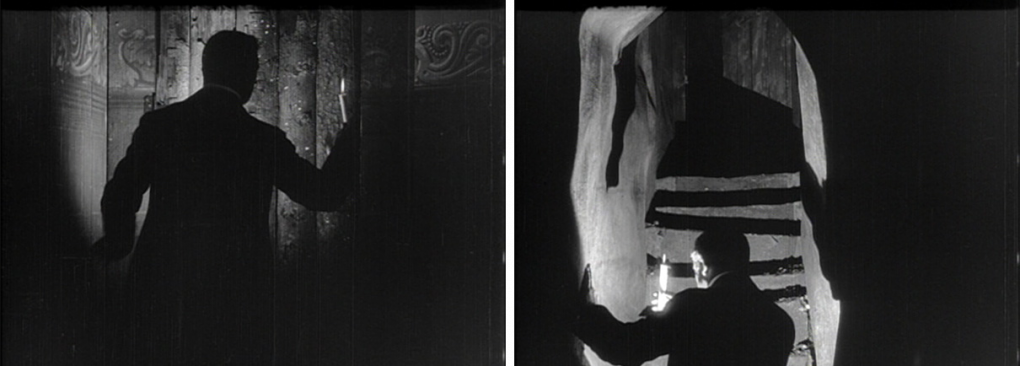

During the 1910s filmmakers around the world explored ways to make their shots more pictorially and emotionally expressive. One frequent path was through unusual lighting.7 The Danish directors were virtuosos in the use of silhouettes and chiaroscuro, and The End of the World doesn’t shirk on this front. The shots of Stoller preparing his escape route in the underground passage are flashy displays of selective lighting, and both the jagged sets and the creeping shadows on the stair look forward to the expressionistic distortions of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.

Blom goes beyond the one-off flashy shot by associating lighting patterns with different situations. In Copenhagen, Stoll and Dina’s home is lit rather flatly, but when they retreat to their mansion in the village, they are swallowed up in dramatic chiaroscuro. The unusual illumination of their parlor prefigures the stark lighting of their escape tunnel, where they will die.

Overall, the harsh lighting associated with the bourgeois contrasts with the simpler, homier lighting on West’s family parlor and the even radiance that will bathe the surviving couple in the final scene.

Scale can be achieved through the scope of the story as well. D. W. Griffith showed that social commentary, the contrasts of rich and poor, exploiter and exploited, could be sharpened through thematic crosscutting. Overall, Stoll’s financial maneuvers run in parallel with the lives of the mining family. On the climactic night, editing powerfully contrasts Stoll’s banquet with the Preacher’s gathering of townsfolk on a hillside. Each man raises his hand, but for Stoll it is a sign of grasping power, while for the Preacher it signifies a benediction.

Deep and wide spaces

All of these efforts to inflate production values encourage monumentalizing other film techniques. This effort alters tactics of staging and camera placement that had been prominent in Danish films of earlier years.

Like other European filmmakers of the period, the Danes exploited the “tableau” aesthetic of lengthy shots with considerable depth of field.8 This approach to filming scenes both interior and exterior has been considered “theatrical,” but it actually relies on the intrinsically cinematic features of the camera lens. The camera’s single eye creates a perspectival space different from the lateral box of the proscenium stage. Danish directors used the deep space of the image for elaborate effects that could never be achieved in theatre.

In addition, Danish directors worked with fairly narrow sets, so they tended to pack their interiors with furniture, knickknacks, wall decorations, and views of adjacent rooms. Within these spaces, actors would perform laterally, in balanced compositions, and in depth, with many areas of the shot being activated. Mirrors, doorways, and windows would allow actors to be positioned at many points of a densely packed frame.

For example, in A Lady of Our Time (Vor Tids Dame, Eduard Schnedler-Sørensen, 1912), a top-hatted figure peeps out from the window behind Anny. A centrally placed mirror registers people coming into the sitting room in Under the Beam of the Lighthouse (Under Blinkfyrets Straaler, Robert Dinesen 1913). A parlor is dotted with various areas of interest in Where Sorrows Are Forgotten (Hvor Sorgerne Glemmes, Holger-Madsen, 1917), and the film’s climax plants a dead man in layers of space, with mourners at different distances and sad-eyed Cecilia dominating the foreground.

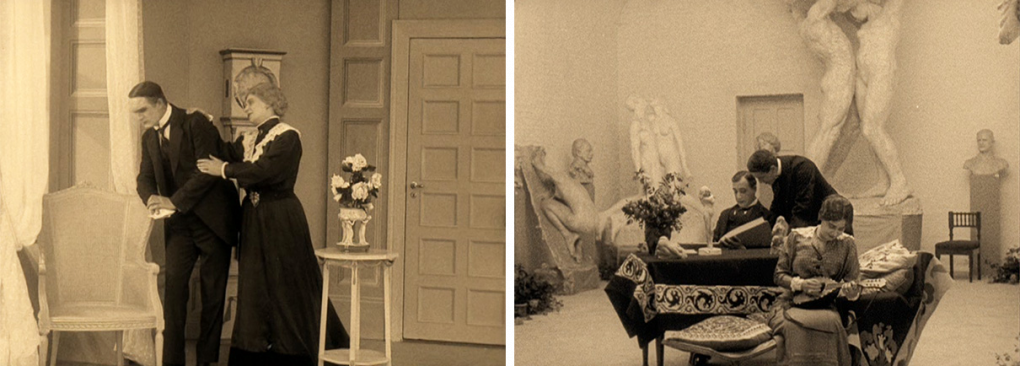

In several films of 1911 Blom had displayed his ability to stage intricate action in tight spaces like these. In the hands of impostors (No. 2) (Den hvide Slavehandels sidste Offer), The Ballet Dancer (Balletdanserinden) and A Victim of the mormons (Mormonens Offer) control the unfolding drama through performance and the choreography of actors within dense sets. In The Prime of Life (Ekspeditricen) gracefully moves five actors around a parlor in several zones of space, with actors turning from the camera to steer our attention to others in the background. Temptations of a Great City (Ved Fængslets Port) uses a less packed set, but it makes virtuoso use of a mirror to reflect offscreen action.

For the big film Atlantis (1913), however, Blom’s staging became more spare and spacious. He posted his actors within simpler perpendicular backdrops, often massive ones shot at a good distance.

He takes the same approach in many stretches of The End of the World.

Although the film is not as pictorially abstract as Atlantis, it employs a fairly open framing strategy, with broader lateral movement of figures. Actors tend to be lined up in symmetrical groups, and the action is highly centered.

Shots like these are far simpler than what we find in Blom’s earlier work, but they are easy to read quickly and so are well-suited to more rapid crosscutting among scenes.

Many directors had made a central doorway or staircase an axis for the whole composition, but The End of the World uses this central vertical strip more than most. Instead of the zigzag depth we find in other Danish films, this is a straight plunge into the distance.

The effect is to make figure movement toward the camera a major means of emphasis. This frontal movement along the lens axis will become central the film’s climax.

That lens axis also governs the film’s editing within scenes. The stress on centered, spacious compositions allows Blom to exploit a technique seen in earlier films but more prominent in the Danish films of the 1916-1918 phase. Again, directors around the world had begun to break up the tableau shot by means of the “axial cut”. This is a straight cut-in or cut-back along the camera axis, without change of angle.

Axial cuts not only emphasize a character’s reaction or a piece of behavior. They also pick up the pace. Along with the film’s rapid crosscutting at the climax, the axial cuts create a faster-moving film than was typical just a few years before. The film’s average shot runs about eighteen seconds, while many Nordisk releases of 1914-1915 average twenty to thirty seconds.9 For a big film, the axial cuts can exaggerate scale; a jump in to a detail or out to a vast crowd has a visual punch.

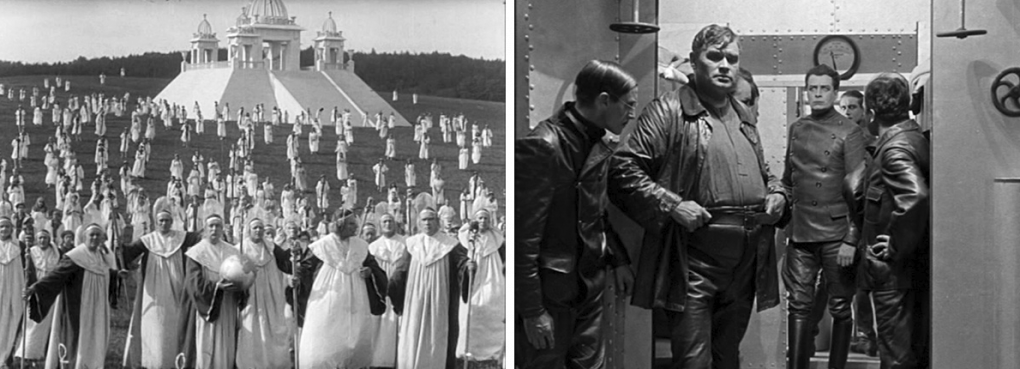

The axial cut comes into its own during the miners’ assault on Stoll’s mansion. The decadent dance celebrating the arrival of the comet is interrupted by the crowd pounding on the salon door. Blom immerses us in the space by showing first the panicky plutocrats, straight to the camera. Men rush to the camera to barricade themselves in, with the camera positioned more or less as the door.

This framing is answered by an axial reverse shot, exactly the opposite framing, and soon by a shot from the outside of the doorway along the axis that both the mob and the partygoers occupy.

To keep the action clear, Blom also provides a profiled shot of the miners smashing the door. But the extension of the axial principle to reverse-field editing creates a very dynamic space that places us in the thick of the attack.

This strategy allows Blom to preserve the wide, balanced compositions favored in the film, along with the constant center-frame strip of frontal character movement. The mansion assault becomes a creative extrapolation of several techniques that give the film a distinctive visual style.

In such ways, Blom is still working with depth techniques, although they differ from the more dispersed, peekaboo compositions of the early 1910s. But at the climax that depth gets canceled by the predominant special effect resulting from the comet’s crash: smoke. Again and again the image gets erased as flurries of smoke eradicate whatever layers of space we can discern. Figures struggle in and out of the murk, only to be engulfed in gray billows. The sense that this calamity has literally wiped out civilization will be confirmed when the image clears in the finale. Returning to the crystalline contours and illumination characteristic of the film’s world before the collision, the devastation stands out brutally.

Windows on a broken world

Blom has internalized the depth aesthetic of the tableau period in a yet another way — one suitable to the grand scale of The End of the World. The effect depends, as so often in early cinema, on windows.

Although the rear window of the West parlor doesn’t yield a view outside, it dominates the first scene set there. When West and the Preacher pray before eating, the framing behind them strongly suggests a cross — a hint about the religious redemption that will come at the end of the film. In later shots of the parlor, varied framings sometimes exclude the window but at dramatic moments it’s activated. The crowd outside confronting Stoll draws Edith to watch from the window, but the curtain is barely opened. Blom saves that for the moment when Edith realizes, in a lightning bolt, the comet’s full fury. And as we’ve seen, the window becomes a locus dramaticus when the flood pours in.

Another window gains prominence in the course of the action. When Stoll tries to calm Dina after her father’s curse on her, an oversize window looks out onto the starry night. (The artificiality of the backdrop might have been less apparent in a tinted print.) That window shows the comet approaching Earth, and after consoling his wife Stoll turns and berates the comet — a moment of lucidity that will be forgotten when he’s celebrating with his party guests.

This splashy shot prepares us for the film’s ultimate window.

The plot’s resolution comes with the reuniting of Reymers, who nearly drowns and is set adrift in a lifeboat, and Edith, who has been rescued by the Preacher. During the attack, crosscutting has paralleled the lovers, each solitary and stranded.

Now they are mystically brought together. The passage recapitulates the film’s design principles.

The very fact of crosscutting prepares us for the couple’s convergence, but Blom’s staging also suggests they are uniting, even when far apart. Edith walks to the camera, and miles away Reymers does the same. As in the sequence of Stoll’s guests and the marauding miners, the frontal movement puts us in between the lovers. Then Edith walks away from the camera, along the central axis, to discover the abandoned church.

Her move into the landscape suggests that Reyners might be just over one of those hills.

Once inside, Edith advances toward us to ring the bell. Cut to Reymers, lying spent on the ground. He is inspired to rise and move toward us. Griffith’s crosscutting tends to show converging forces through diagonal or lateral movement, preparing us for characters or vehicles to intersect. Blom prepares us for the same thing by adapting his tableau’s bias toward axial movement to the logic of crosscutting.

Then, in a brilliant stroke, Blom has Edith move to the window of the belfry, which has been patiently waiting behind her. She looks out. An axial cut takes us to a bold depth shot. We see, tiny but discernible, Reymers making his way to her.

The vast space of the plain has replaced the jammed areas that would have been typical of the earlier Nordisk deep space. A single figure dwarfed by the landscape becomes the focal point of the story’s emotional impact. Going very wide and very deep, Blom might say, allows you to stretch the tableau style to blockbuster proportions.

If The End of the World is a well-fleshed-out prototype of the apocalyptic disaster movie, what are we to say about another Nordisk effort to capture the audiences of war-torn Europe?

As the company began to slump from 1917 on — losing national markets , its films banned in various countries — the firm’s output declined. That did not stop company director Ole Olsen from betting on another superproduction, A Trip to Mars (Himmelskibet, Holger-Madsen, 1918). In the process, he came up with another genre, the science-fiction space opera. With its comic-book exaggerations (the hero is named Avanti Planetaros) and its pacifistic, vegetarian Martians in white robes, it looks forward to the utopian communities visited by Star Trek missions. But its polished staging featuring vast crowds and relentlessly frontal and tunnel-vision compositions suggest that Blom’s handling in The End of the World provided Nordisk a new “house style” suited to ambitious productions.

It may also have yielded proof of concept for the more elegant Dickens adaptations by A. W. Sandberg in the 1920s.

Unfortunately, The End of the World was not enough to rescue the failing company. But this daring film and many other superb pieces of cinema remain as reminders that this era of Danish films harbors many treasures. Thanks to the enterprising archivists at the Danish Film Museum, all we have to do is look.

Thanks as ever to Thomas Christensen, Mikael Braae, and their colleagues for helping me gain access to the splendors of Danish cinema.

Notes

1. See the video lecture “How Motion pictures became the movies,” at http://www.davidbordwell.net/blog/2013/01/12/what-next-a-video-lecture-i-suppose-well-actually-yeah/.

2. Isak Thorsen, “The Rise and Fall of the Polar Bear,” in 100 Years of Nordisk Film, ed. Lisbeth Richter Larsen and Dan Nissen, Copenhagen: Danish Film Institute, 2006, 59-62.

3. “Verdens Undergang”, entry in Marguerite Engberg, Det Danske Stumfilm 1903-1930, Copenhagen: Danish Film Museum, 1968, 36.

4. See for example Ebbe Neergaard, The Story of Danish Film, Copenhagen: Danish Institute, 1963, 49-54.

5. Isak Thorsen suggests that historians who attribute Nordisk’s failing fortunes after 1915 to artistic decline have played down stronger causes, such as the closing of international markets and other economic factors. Thorsen points out that Nordisk’s management encouraged directors and staff to innovate in the face of competition. The End of the World would certainly fit that mandate. See Thorsen, Nordisk Films Kompagni 1906-1924: The Rise and Fall of the Polar Bear, Herts: John Libbey, 2017, 190-201.

6. Reviews can be found at

https://archive.org/details/motography152elec/page/1165/mode/2up?view=theater.

https://archive.org/details/motionpicturenew133unse/page/3092/mode/2up?view=theater.

https://lantern.mediahist.org/catalog/movpic28chal_0503.

7. See Kristin Thompson’s essay “The International Exploration of Cinematic Expressivity” in Film and the First World War, Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 1995, ed. Karel Dibbets and Bert Hogenkamp, 65–85.

8. See my “Nordisk and the Tableau Aesthetic” at http://www.davidbordwell.net/essays/nordisk.php. On tableau staging generally, see my On the History of Film Style, 2d ed., Madison: Irvington Way Institute Press, 2018 and Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005. See also the tag “Tableau Staging” on “Observations on Film Art” at http://www.davidbordwell.net/blog/category/tableau-staging/.

9. Interestingly, at an average shot length of sixteen seconds, Blom’s Atlantis is cut slightly faster than The End of the World.

Illustrations

Illustrations without captions are all framegrabs from The End of the World (Verdens Undergang, August Blom, Nordisk Films Kompagni 1916).

David Bordwell, Professor Emeritus | 22 April 2021