When short comedies were squeezed into cinemas

Jeppe Mørch, Journalist | 1 April 2020

The terms ‘forcemeat stuffing’ and ‘farce’ both stem from the Latin verb ‘farcire’, meaning ‘to fill up’ or ‘to stuff’, and this is actually how such short comedies were used in Danish silent film cinemas. These small lively films of tomfoolery functioned to fill the gaps in the evening schedules of the era. Either they were squeezed into a cavalcade, or they could be served as a quick hilarious dessert after a larger main course, which at that time often consisted of a romantic drama.

The farce takes shape

At the first ever cinema screening – on 28th December 1895 in the Grand Café – the Lumière brothers already had farce on the menu. They squeezed in L'Arroseur Arrosé as film number six of nine in which many features of the short comedy are introduced when a mischievous scamp jokes around with a gardener.

The man at work is watering a flowerbed as a boy enters the picture with a desire to play tricks. He places his foot on the hose, stopping the water and causing the unsuspecting gardener to gaze incredulously into the nozzle. Then the boy releases his foot and the gardener gets soaked. The scene ends with a short chase – the gardener runs after his tormentor whose punishment should, naturally, be a beating. In other words, a cunning plan, its execution, a hot-headed victim, a confrontation, and a chase were the ingredients making up the farce from the very beginning of cinema.

In Denmark, too, a quarrel and the question of who knows what when became the simple dramaturgical driving force in comic silent films. But alcohol more often than water kicked off the shenanigans in Danish cinema.

Slave to the situation

But before scheming men fuelled by schnapps began conspiring against their wives in smoky pubs, the Danish audience was presented with even simpler trouble brewing. In the two-volume Dansk stumfilm (‘Danish Silent Film’), the pioneering film researcher Marguerite Engberg identifies situation comedy, based on a single funny idea, as the simplest of the short comedies.

In Den nærsynede Guvernante (The short-sighted Governess) in 1909, the title character insists on reading a newspaper even though she is wandering around a park with a little girl under her responsibility. Naturally this distracts the governess and she gets into trouble by sitting on a freshly-painted bench before the stupidity culminates in her taking the wrong child home to her employers, the girl’s parents. Each scene is self-contained, showing one problem of being distracted and visually restricted at the same time. A cut indicates a new scene and an escalation of the premise.

Throughout the film, the protagonist wears a pompous floral hat, and that seems to have been a common attitude among filmmakers of the time: if there’s fun, there’s a hat!

That exact idea makes up all of A New Hat for the Madam from 1906. A young woman chooses a grotesquely huge hat at the milliner and then destroys both her Victorian style home and the streets of the city with her monstrous headgear. The film is directed by Viggo Larsen, who is also the man behind The Witch and the Cyclist (1909). Engberg praises the latter as "the niftiest farce that Nordisk Film has ever produced". Bearing in mind the technical limitations of the time, you can't help but be impressed by the film’s ingenuity. A mischievous witch uses her dark magic on an innocent cyclist until he is all confused. He is forced to pedal backwards as his bicycle changes shape on the witch's command.

There were also action/adventure farces. Anarkistens Svigermor (‘The Anarchist’s Mother-in-Law’ – 1906) is one example. The film portrays a stressed man who eventually chooses to blow up his wife’s mother with dynamite to restore peace at home.

The Governess and the Anarchist came out over 100 years ago, but the ideas behind them do not yet seem completely outdated. Nowadays in 2020 we have hardly heard the last joke about an annoying mother-in-law, and if the newspaper is replaced with an iPhone, the obliviousness suddenly becomes recognizable.

They’re just characters

If a comedy filmmaker kills a woman with dynamite, it is vital the audience does not cherish warm feelings towards the deceased. In farce films, it must not sincerely have been a pity for anyone, so the screenwriters and directors worked with characters – not with actual, nuanced people.

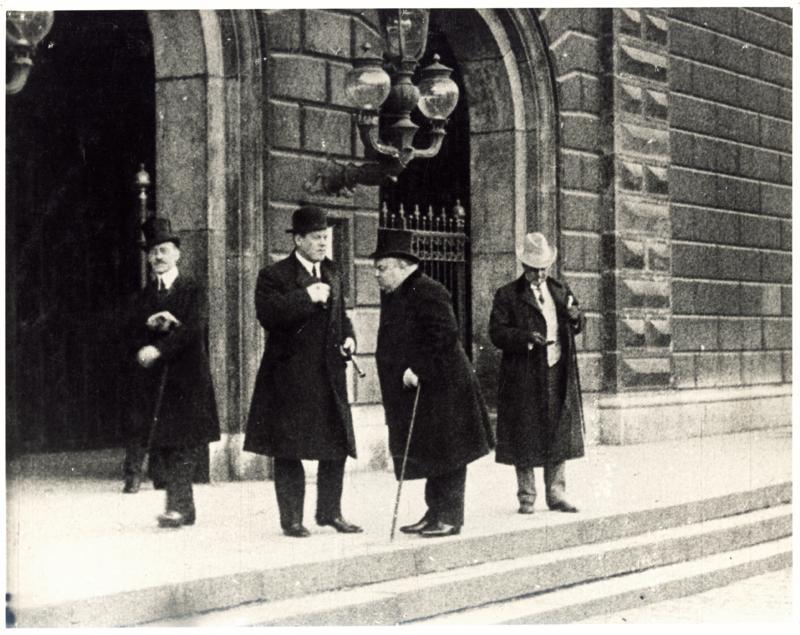

This is particularly evident in Carl Alstrup’s København ved nat (Copenhagen By Night, 1910), where drunken men with no past nor future are able to romp around for 25 minutes. They do not represent alcoholism, personal problems or other dark sides of tavern life. They just want to dance and drink. Film researcher Ron Mottram is unenthusiastic about the escapades. “Overall, the film has little to recommend it,” he writes in The Danish Cinema Before Dreyer, yet it would be difficult not to crack a smile at the spherical Oscar Stribolt’s ability to flounder and grimace like a drunk.

Stribolt plays the fool beautifully throughout an incredible number of silent comedies, and underneath a photograph of him in swimwear, Marguerite Engberg writes in her book: “Fat actors have always been popular in this country”.

A few months before the premiere of København ved nat (Copenhagen By Night), Urban Gad’s iconic romantic drama Afgrunden (The Abyss) had been screened to enthusiastic audiences. When Alstrup crams a ‘lizard dance’ and ‘sucking waltz’ into his drinking farce, it can be taken as a satirical nod to Asta Nielsen and Poul Reumert’s racy gaucho dance in The Abyss.

Ungkarl og ægtemand (1915, The Grass Widower) and Flyttedags-Kvaler (1915, Moving Day) are both about men who are a little daft and have a little desire to get away from their wives at home. Out of the picture are the horrors and trenches of the First World War that other films of the day were about. Instead, the farce unambiguously engages in a man’s constant desire to escape from the petty annoyances of everyday life. Young women and whiskeys are more fun than moving house and marriage is the carefree message.

Farcical comedies on the assembly line

The moving house comedy was directed by the highly prolific Lau Lauritzen Sr. After a brief military career in the early 1900s, Lau began tinkering with the acting profession and screenwriting, and was soon hired as a director by one of the world's largest film companies, Ole Olsen’s Nordisk Films Kompagni, where from 1914 to 1919 he produced about 200 comedies. He later switched to Palladium to establish the duo Fy and Bi as comedy stars in the 1920s.

With Don Juans Overmand (The Love Potion) in 1916, Lau Lauritzen Sr. created a successful farce-fuelled comedy about a young pharmacist, Peter Pille, who wants to marry the niece of Colonel Sejsberg (Oscar Stribolt). Unfortunately, the colonel turns out to be obstructive. He lacks popularity with women himself, so cannot bear to see others enjoying themselves. That might all change if Mr. Pille can conjure up an elixir that made young women drool over an old military man...

We are still far from an attempt at complex characterisation, and there are noticeable caricatures in Lauritzen’s Min Svigerinde fra Amerika (My Sister-in-law from America, 1917), where a brother living in the USA returns to Denmark as a rotund Uncle Sam, complete with hat (of course) and vandyke beard.

Without sound it can be difficult to make fun of dialects, but with the non-standard Danish title Je' sku' tale me' Jør'nsen (I Want to Speak to Johnson, 1917), the railroad track grinder Nokke’s proletarian Copenhagen accent still draws attention. Nokke is looking for his friend called Jørgensen, who has had a drop too many until he’s seeing flies and elephants – and then risks being institutionalized.

None of the comedies were made to be critically evaluated more than 100 years later, but they can certainly be seen as a happy play around with an early medium. They must have realised back then that there is a much greater opportunity to move in front of a camera than on a theatre stage. The actors run around plenty in the farces in any case!

Was that supposed to be funny?

Lau Lauritzen Jr., son of Lauritzen Sr., who became an actor and director, is perhaps unsurprisingly positive in a review of his father’s films. In the book 50 aar i dansk film (‘50 Years of Danish Cinema’), he describes Lau Sr.’s farces and comedies as “always pure, always conveying a mood that alternated between the eccentric, the good-natured, the satirical and not least the compassionate”.

Marguerite Engberg in turn appraises Lau Lauritzen Sr. using what would be called a shit sandwich in present-day management speak. The films “can be described as pleasant, often with a rather comical plot, but Lau Lauritzen never found any real sense of timing. Although it must be said that he gathered a rich and witty gallery of characters”.

From our contemporary perspective the acting style of the short comedies may seem exaggerated given every interaction ends with violent gesticulation and wild grimacing. But it must be remembered that both dramatic and comedic actors came from the theatre where the distance between stage and audience necessitated grand gestures and clear facial expressions.

Even then, this style gave rise to discussion about moderation. In the book Filmen. Dens midler og maal (‘Film. Its Means and Objectives’) from 1919, Urban Gad pours scorn on “coarse farces” and pleads for comedy as this must be regarded as “an art form that is particularly good for cinema”. Less rough-and-tumble and more restraint, please. But Gad acknowledges that the balancing act can be tricky: “Comedy is a difficult plant to grow; it withers in drought, and dies when watered.” In 1926, Gad was even allowed to try his hand at the world of Fy and Bi when he directed Lykkehjulet (The Wheel of Fortune).

That moderation should be the only proper path to comedy of artistic quality was later contradicted by the renowned formalist film theorist Rudolf Arnheim. “It is, of course, understandable that a medium so strongly dependent upon the visible – particularly in the case of the silent film – will easily induce the actor and the director to give strong prominence to facial expression and gesture. Slapstick shows with especial clearness how very suitable to film is this exaggerated play of feature and limb,” he writes in the book Film as Art. But he was obviously thinking more of Chaplin than Danish farces.

From stuffing to main course

It’s been a long time since comedy was reduced to stuffing used to patch holes in the schedule. The three best-selling films in Danish history are all ‘Olsen gang’ comedies, followed by Op på fars hat (Walter and Carlo – Up On Daddy’s Hat) and Ternet ninja (Checkered Ninja). Casper Christensen and Frank Hvam’s three Klown films have sold over 1.7 million tickets combined.

Comedy has become a chosen main course.

The 1910s’ caricatures of constantly gesticulating boozy blokes sporting tiny bowler hats on big faces might be difficult to mimic precisely. Nevertheless, many of today’s immensely popular comedies can be considered a further development of those past themes.

Just think of the Klown universe, awash with alcohol and digressions. Casper and Frank aren’t allowed just to be happy and drunk for much time at all. There is always a price to pay when you carry on as a clown.

The denial of responsibility never becomes embarrassing in the same way for an Oscar Stribolt character in the scarce few minutes of a silent film farce. Sure, his wife is angry when he comes home in København ved nat (Copenhagen By Night), but when he’s asleep in bed, completely exhausted by beer and dancing, it’s over. There is no tomorrow. No hangover. That might explain the carefree thirst of these silent film funny guys.

Jeppe Mørch, Journalist | 1 April 2020