Danish silent film during World War I

Bjarne S. Bendtsen, Associate Professor | 15 January 2020

In the years leading up to the outbreak of World War I in August 1914, Denmark had one of the leading film industries worldwide, with Ole Olsen’s (1863-1943) Nordisk Films Kompagni as the largest company. The war put an end to this. Access to foreign markets was made more challenging by the war, and the war’s impact on the huge German market reduced demand there. After the war ended in November 1918, other film industries had taken over, in particular the USA.

Danish War Films Before 1914

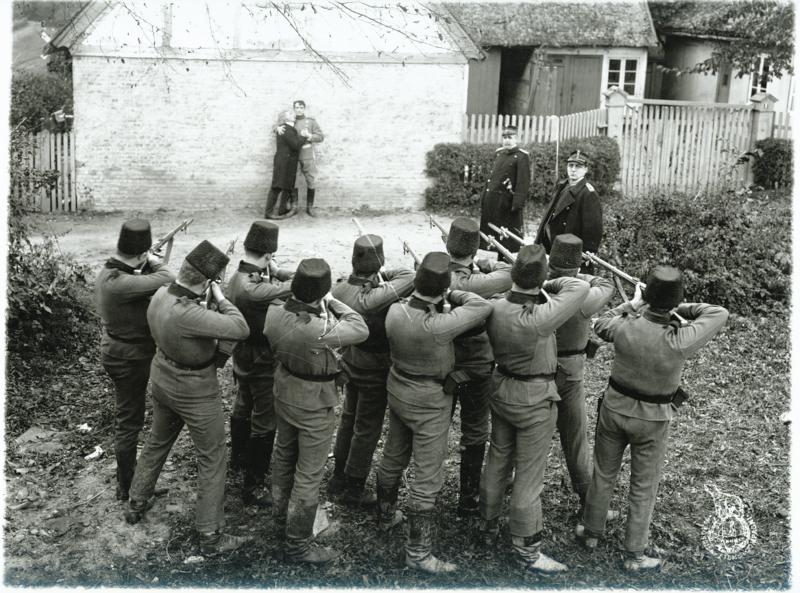

Some of the first major Danish film productions were war films, including a small wave of films from 1909-1912 about the Schleswig Wars. The most significant of these is the film adaptation by Eduard Schnedler-Sørensen (1886-1947) of the highly popular patriotic poem Den lille Hornblæser (The Little Bugler, 1909), which at the time was the world’s longest film with just over 20 minutes of running time. It became Denmark’s success of the year, about which the Social-Demokraten newspaper in spring1910 reported, “over a quarter of a million people have now seen the national success The Little Bugler.”2 The following year, Urban Gad (1879-1947) and Alexander Christian (1881-1937) directed En Rekrut fra 64 (A Recruit from 64),3 which ends with the hero Felix clenching “his hand menacingly towards Germany and exclaiming, ‘If only I could take revenge!’”. This sharp anti-German angle and rhetoric understandably disappeared from Danish films with the outbreak of war. In 1910, Gunnar Helsengreen (1880-1939) directed En Helt fra 64 (A Hero from 64)3b as a kind of sequel to Den lille Hornblæser (The Little Bugler), but the film, described in its programme as a “National War Drama”, was apparently not a success. Finally, H.O. Carlsson’s Fæstningsmanden or Minder fra 64 (The Reservist or Memories from 64) premiered on 18th March 1912; a “military history play” with episodes from the retreat from Dannevirke and the 1864 war, according to the poster.

Yet during these years, more than only serious historical films about war and the military were made. The Danish tradition of soldier comedies – best known for Sven Methling’s film series Soldaterkammerater (Soldier Comrades) (1958-1968) – actually dates back to the infancy of film. Among others this included Nordisk Films’ Soldatens glade Liv (The Soldier’s Happy Life, 1910); Schnedler-Sørensen’s unmilitary farce Carl Alstrup som Soldat (The Actor As Soldier, 1911), where the popular performer Alstrup avoids further military service by playing the idiot; 4 Filmfabrikken Skandinavien’s Pigernes Jenser or – again – Soldatens glade Liv (The Soldier’s Happy Life, 1912): a “cinematographic farce” about four old soldiers who have been recalled, but only after getting drunk “in the happy Copenhagen Anno 1912-13”; and slapstick comedy Frederik Buch som Soldat (Fred As Soldier, 1913), directed by Christian Schrøder (1869-1940), with actor Frederik Buch playing the role of an impossible recruit – the film’s alternative title is Rekruttens Genvordigheder (The Recruit’s Tribulations). Even during the war, this light-hearted approach to the subject is found in Kystartilleristens glade Liv (The Coastal Artillerist’s Happy Life) – with the alternative title Carl Alstrup i Sikringsstyrken (Carl Alstrup in the Security Force) – which premiered on 28th May 1917.5 Finally, Schnedler-Sørensen’s Vennerne fra Officersskolen (Crossed Swords, 1913) is categorized as a war film on this website and strikes a slightly more serious tone than those previously mentioned.

Spy Films: Films from the Balkan Wars and Sealed Orders (1914)

In the years leading up to the First World War, the output of Danish war films took on a far more serious tone, with a bleaker interpretation of war and the military: the Balkan Wars of 1912-13. Den kvindelige Spion fra Balkan or Generalens Søn (The Female Spy from the Balkans or The General’s Son), whose director is unknown, premiered on Boxing Day 1912, just over two months after the first Balkan War had broken out on 8th October 1912. It is a melodramatic spy story, in which, judging by the film programme, the most commonly used Balkan setting was considered an exotic spot. Three days previously, Urban Gad’s Pigen uden Fædreland (The Girl Without Fatherland) had its Danish premiere; it was, however, recorded in Berlin as Das Mädchen ohne Vaterland. The film was the latest Asta Nielsen success, as described in a cinema advert, and was based around an episode from the Balkan War where Asta Nielsen (1881-1972) plays a gypsy girl in a melodramatic love and spy plot.6

The following year, Vilhelm Glückstadt (1885-1939) directed Krigskorrespondenter (War Correspondents), which premiered on 13th May 1913. A newspaper advert for the film’s release at the Victoria Theatre described it using cinematic clipped fragmented phrases such as “an image of the horrors of modern war. A railway bridge collapses, a warship is blown up, an aeroplane is shot down etc. etc.”7 Naturally, perspectives critical of war already existed before the war; not merely on the moral basis resorted to by several Danish war films from the period, but also as a commercial draw. Another film about the Balkan Wars is Adrianopels Hemmelighed (The Secret of Adrianople) by Einar Zangenberg (1882-1918), which had the alternative titles Spionen (The Spy)and Flugten paa Liv og Død (The Flight of Life and Death). The film, which according to the programme concerns an “episode from the Turkish War”, premiered on 13th October 1913, and might also be referred to as a spy film. The same applies to Den kvindelige Spion fra Balkan (The Female Spy from the Balkans) and later films such as De røvede Kanontegninger (The Stolen Siege Gun Plans)byA.W. Sandberg (1887-1938) or Mit Fædreland, min Kærlighed (Through the Enemy’s Lines) by Robert Dinesen (1874-1974), which also had the title Spionen (The Spy).

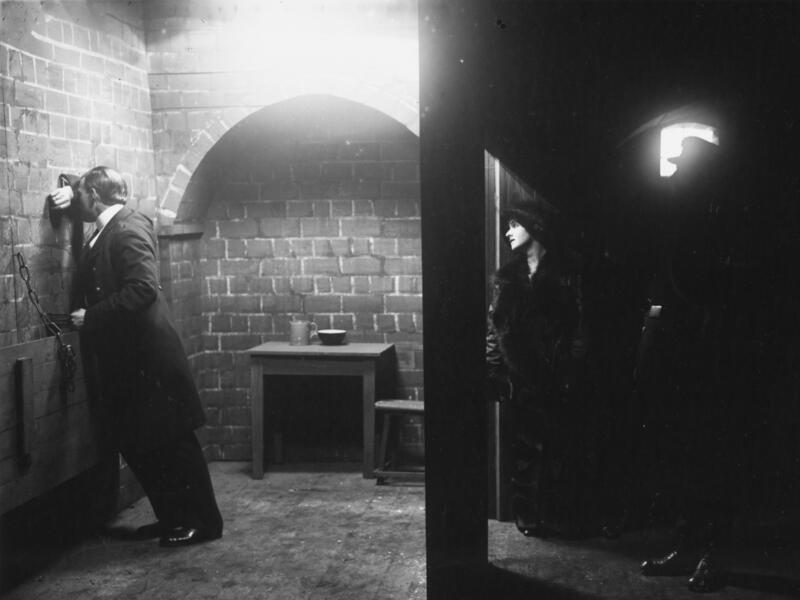

In addition to the aforementioned films from the Balkan Wars, Benjamin Christensen’s Det hemmelighedsfulde X (Sealed Orders, 1914) belongs in the spy film category. It opens with the hero, Lieutenant von Hauen, who writes his will as the danger of war is imminent – and indeed, it is not long before war breaks out. The film has a somewhat sensational, unrealistic, melodramatic plot – but it also features several cinematically beautiful sequences, not least Christensen’s use of light and shadow, which has been acclaimed for its quality.

Pacifist War Films: Lay Down Your Arms! (1914) and Pax Æterna (1917)

The pacifist war films recorded in Denmark during these years are more substantial. One of the world’s first pacifist films is Ned med Vaabnene! (Lay Down Your Arms!), which was directed by Holger-Madsen (1878-1943) – also known as “Holger Bindestreg” (“Holger Hyphen”) after he changed his name in 1911 – with a script by Danish film’s up-and-coming international star directors, Carl Th. Dreyer (1889-1968). It is a film adaptation of the anti-war tome Die Waffen nieder! (1889) by Austrian Baroness and Nobel Prize winner Bertha von Suttner (1843-1914). The film should have premiered at the 21st International Peace Congress in Vienna on 15th-19th September 1914, in honour of von Suttner herself, who had been awarded the title of President of Congress.8 Understandably, this did not come to pass: the Congress was cancelled, and moreover, perhaps mercifully, von Suttner died on 21st June 1914 – before shots were fired in Sarajevo and the war rebutted her advocacy and hope for a peaceful future.

In 1914 Lay Down Your Arms! was classified with the then rare censorship category: prohibited for children under 16. Owing to the outbreak of war, it first premiered in Denmark on 18th September 1915.9 A reviewer in Politiken newspaper wondered the day after the premiere about the purpose of the age restriction: the reviewer writes there is nothing in the film “that can exert undue influence, except perhaps on very little ones, for whom the effects are probably too violent”. But continues, “older children could learn from this series of images to hate war, its brutality and barbarism, its destruction and curse.”10 The reviewer also correctly predicts the film’s success. Contemporary publicity mostly concerned itself with the grand nature of its magnificent spectacles, with its important war-critical message, and with its “incomparable realism”, which was also highlighted in both the Danish and English-language programmes. 11For a modern audience, the film appears violently melodramatic – the same goes for von Suttner’s novel, of course – and the image of war it creates does not match the mechanized, industrialized slaughterhouse of the world war at all.

Lay Down Your Arms! was not the only Danish pacifist war film – though perhaps more precisely, they should be referred to as peace films, since to a much greater extent they depict the struggle for peace. The most significant is Holger-Madsen’s drama Pax æterna, which at its sold-out premiere at the Palace Theatre on 16th February 1917 opened with a prologue written by the author Sophus Michaëlis (1865-1932) “voiced with Power and Pathos” by the film’s director.12

Pax æterna opens with an old king in a happy country, the Prince of Peace, being forced to go to war with a neighbouring country. He immediately dies of a heart attack and his young son, Alexis (who is in love with the film’s heroine, Bianca, the daughter of old pacifist Professor Claudius) has to reluctantly wage war. The young king expels his enemies from the country, but then refuses to continue the war as his government demands. Instead he is actively involved in pacifist work for which Bianca and the Red Cross have been taking the lead. They equip a peace ship and summon all the world’s nations to a major peace congress where global leaders sign the peace treaty ensuring Eternal Peace, which is one of the film’s alternative titles.

War, Patriotism, and Love: Through the Enemy’s Lines (1915) and Pro Patria (1916)

However, not only pacifist war films were made in Denmark in the 1910s, but also patriotic films often swathed in melodramatic love stories. A good example is Mit Fædreland, min Kærlighed (Through the Enemy’s Lines, 1915) – a three-act war drama based on true events. The film’s programme describes it as “an officer’s love novel during the war” and a “great military folk play about a brave officer and his heroic girlfriend.”13 The film has the alternative title Spionen (The Spy) which, along with its English title Through the Enemy’s Lines, both draw more attention to the film’s spy plot than the original Danish title ‘My Fatherland, My Love’.

A similar but more significant film is Pro Patria (August Blom, 1869-1947) which premiered in Denmark on 21st February 1916. Like much Danish treatment of the war, this film is quite a melodramatic and unrealistic account, where individual heroism is still crucial to the outcome of the fight. The film has the great actor of his time Valdemar Psilander (1884-1917) starring as protagonist Erich von Wimpfen, Alma Hinding (1882-1981) as Else, and Gunnar Sommerfeldt (1890- 1947) as Alexis, and it was a fairly big success in Danish cinemas.14

Similar features are seen in Robert Dinesen’s I Farens Stund (The Fortunes of War), released in Denmark on 22nd November 1915,15 and in Holger-Madsen’s Krig og Kærlighed (War and Love), released on 23rd September 1918. The latter is about a young officer who is torn between love and his duty to the fatherland – and the moral is crystal clear: a soldier’s duty to the fatherland surpasses everything else, even love. In September 1918, however, this 1914 dilemma did not seem to appeal to the audience. This may be due to the fact that the film – along with Pro Patria, Mit Fædreland, min Kærlighed and De røvede Kanontegninger, above – was actually recorded earlier in the war, as early as the autumn of 1914, when Nordisk Films sought to exploit the success that Lay Down Your Arms! had achieved in the United States.As the film historian Marguerite Engberg has astutely stated in an article on Krig og Kærlighed, it then became “difficult to accept Nordisk Films Kompagni’s ‘operetta officers’ when the world war broke out.”16 After praising Holger-Madsen’s impressive staging and similarity of war scenes to The Birth of a Nation (1915) by D.W. Griffith (1875-1948), she writes that Lay Down Your Arms! nonetheless does not feature Griffith’s incomparable dramatic cutting techniques:

However, it is not down to form that the film struggles to captivate today. There is something wrong with the content. The action lacks any basis in reality. The film shows operetta soldiers and operetta officers and the action centres around a General Tilling, whose private life story should interest us more than the war itself. Neither Baroness von Suttner nor Holger-Madsen had the sufficient ability nor imagination to envisage what dread and horror a modern war entailed; the battle scenes that would have seemed realistic and powerful on pre-World War I audiences appeared naive and somewhat unconvincing a few years later.17

This is characteristic of many of these films. Engberg continues her analysis especially of Nordisk Films’ war films as follows:

Another reason why the portrayal of war seems artificial is that the action, as had become customary at Nordisk, is set in an unspecified country. In worrying about potential audiences of the film, they had taken care to ensure uniforms and names were sufficiently indeterminate so no one should feel uneasy. But this meant that the film’s problems became unrealistic and bland.

With good reason, these shortcomings did not become less prominent as the war progressed. Even in Denmark, cinema audiences had the opportunity to see The Battle of the Somme (1916) – the extremely popular British documentary (with recorded fictional scenes) – for example.

Sci-fi Pacifism: A Trip to Mars (1918)

A somewhat different approach to criticism of war is found in Holger-Madsen’s sci-fi-film Himmelskibet (A Trip to Mars, 1918). Sophus Michaëlis’ prologue links the film with war: “What we built up, we broke into pieces / – a Ragnarök rages across the earth, / mutilated, the world lifts its crutches / towards the distant peaceful oases of heaven.”18 These peaceful oases are the goal of the film’s hero, Naval Captain Avanti Planetaros, and there he and the crew of the celestial ship Excelsior encounter a far more advanced and peaceful civilization – paradoxically enough on Mars.

A lengthy review in Politiken newspaper the day after its premiere starts by describing the Copenhagen film audience as whimsical: “They stormed the cinema to see a silly speculation film but they did not quite fill the Palace Theatre last night, even though an outstanding Danish author’s name was on the programme.”19 The reviewer remarked on Michaëlis’ short prologue: “To a backdrop of the horrors of war, the poet lifted his gaze to the twinkling stars and prophesied that the feat would one day make the leap now dared by the imagination.” But this scene is also the problem with the film, in the reviewer’s opinion, since it was not quite possible to portray Michaëlis’ beautiful thought: the idea behind Himmelskibet “could have become a beautiful poem”, but instead it has “become an entertaining film”. The different art forms are clearly not considered equal at this early stage in the history of cinema.

Revolutionary Consequences of War: A Friend of the People (1918)

Finally, there are films that deal with war as a theme in a more derivative manner. At the end of 1918, Holger-Madsen directed Folkets Ven (A Friend of the People), which was released on 2nd December 1918, shortly after the end of the war. In terms of genre, it is described on the poster as “a society film” and in the programme as a “society play”. The protagonists symbolically have the surname Kamp (in English: Battle) and the film’s plot in short is as follows: the three Kamp brothers want social change, but choose different means to achieve it. Blacksmith Waldo, played by Svend Kornbeck (1869-1933), wants revolution; the weak disabled watchmaker Kurt, played by director Holger-Madsen himself, tries to shoot the country’s Prime Minister, who ironically is saved by his pocket watch – in an echo of Council President Jacob Brønnum Scavenius Estrup’s survival of an assassination attempt by his coat button just over 30 years previously – but the film’s hero, typographer Ernst, played by Gunnar Tolnæs, believes that societal change must come through legal, democratic means.

Towards the end of the film, Ernst Kamp, now the leader of the People’s Party and a minister in Prime Minister Truchs’ government, gives a speech at Folkets Park (‘the People’s Park’). A series of clips almost act as a taster of Social Democratic propaganda in later years, showing how things used to be, and what progress has been made through the work of the party – within the framework of the law, which is the film’s key message for the revolutionary contemporary. The hero then ends up with the Prime Minister’s daughter, sealing the new social order and fraternity between the upper class and the workers.

Successors to First World War Films

Once the cannons of the world war battlefields had fallen silent in November 1918, audiences were tired of war. The topic only became relevant – or financially appealing – again several years later, primarily in association with the great war book boom that arose around the tenth anniversary of the ceasefire. Some war films were made before the boom in the late 1920s, such as Rex Ingram’s The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921) with the up-and-coming superstar Rudolph Valentino, but the number of war films increased dramatically around 1930. Lewis Milestone’s Oscar-winning Hollywood version of the German novel Im Westen nichts Neues (All Quiet on the Western Front) by Erich Maria Remarque, first published as a newspaper serial from November 1928, was a huge success. All Quiet on the Western Front had its world premiere in the USA on 25th April 1930 and was released in Denmark the same year on 1st August. Another significant work that contributed to the start of the war book boom is British R.C. Sherriff’s play Journey’s End that premiered in London on 9th December 1928. The play was adapted for film by James Whale and released in cinemas in April 1930. These war films worked particularly well at the time for the simple reason that the ‘talkie’ had arrived: the battle scenes had sound.20 Ever since, the war film has been a regular fixture at the cinema, because war never goes out of fashion. Even at the time of writing, Sam Mendes has just been awarded a Golden Globe for his war drama 1917 (2019).

Notes

2. Social-Demokraten, 13 March 1910, p. 1.

3. The programme – and film – can be viewed at: https://www.stumfilm.dk/stumfilm/streaming/film/en-rekrut-fra-64.

3b. The programme – and a fragment of the film – can be viewed at: https://www.stumfilm.dk/en/stumfilm/streaming/film/en-helt-fra-64.

4. See https://www.dfi.dk/viden-om-film/filmdatabasen/film/carl-alstrup-som-soldat.

5. See https://www.dfi.dk/viden-om-film/filmdatabasen/film/kystartilleristens-glade-liv.

6. Filmen, årg. 1, nr. 6, 1. januar 1913, s. 90-91. Se desuden https://www.dfi.dk/viden-om-film/filmdatabasen/film/pigen-uden-faedreland.

7. Nationaltidende, 19 May 1913, morning edition, p. 4..

8. cf. Andrew Kelly: ‘Film as Antiwar Propaganda. Lay Down Your Arms (1914)’, in Peace & Change

vol. 16, nr. 1, Jan 1991, pp. 97-112.

9. cf. https://www.dfi.dk/viden-om-film/filmdatabasen/film/ned-med-vaabnene.

10. Politiken,19 September 1915, p. 9.

11. The various programmes are found on Stumfilm.dk: https://www.stumfilm.dk/stumfilm/streaming/film/ned-med-vaabnene.https://www.stumfilm.dk/stumfilm/streaming/film/ned-med-vaabnene

12. Politiken, 17 February 1917, pp. 2-3..

13. The programme can be downloaded here: https://www.dfi.dk/viden-om-film/filmdatabasen/film/mit-faedreland-min-kaerlighed (04.01.2020). The digital edition of the film is Dutch, in which the characters have other names than in the programme.

14. For example, see advert in Berlingske Tidende, 1 March 1916, p. 4.

15. See https://www.dfi.dk/viden-om-film/filmdatabasen/film/i-farens-stund.

16. Marguerite Engberg: Dansk stumfilm – de store år (1977), bd. 2, p. 509.

17. Ibid., p. 504.

18. Programme and prologue etc. can be found at: https://www.stumfilm.dk/stumfilm/streaming/film/himmelskibet.

19. Politiken, February 1918, p. 10.

20. For example, see Povl Westphall’s review of the German documentary Im Trommelfeuer der Westfront in the south Jutland war invalids’ magazine Krigs-Invaliden, 13. årg., nr. 9, 1 December 1936, pp. 89-90.

Bjarne S. Bendtsen, Associate Professor | 15 January 2020

The Great War on the big screen

Produced by Liv Thomsen ('Historieselskabet', 2020).